Why Taylor Swift Is the Super Bowl of Pop

In the music industry today, there’s the 1 percent, and there’s everybody else.

Why is this woman gloating?

Taylor Swift is exulting because Billboard and Nielsen SoundScan finally made it official: Last week, defying early predictions, Swift’s fifth studio album, 1989, sold enough copies in the U.S. to go instantly platinum. In its first week on sale, the album shifted 1.287 million units, to be precise, giving it the highest week of sales by any album since 2002’s The Eminem Show.

Album sales, in this age of easy streaming, are down 14 percent this year. And yet Swift’s 2014 album opened even bigger than her last one did. How did she pull that off? Part of the answer is unique to Swift, but not all of it. What’s happening in the music business is deeply redolent of our winner-take-all, 1-percenter economy. There’s a tiny handful of musical-cultural conversations Americans have decided they want to be a part of, and then there’s everything else.

In order to understand this, it’s important to put Swift’s sales number in context. Word of her impressive tally has been all over the press as the reported estimates kept rising, but much of the media shorthand has failed to capture just how exceptional Swift’s sales are, either historically or for an album released in 2014, an appalling year for the music business. Billboard has all the details on the Swift album’s string of milestones, but I’m going to recap and frame them in order of remarkableness:

One of only 19 albums, ever, to sell a million in a week: The club of artists able to shift a million albums in seven days is a truly exclusive one. Swift is not new to that list; in fact, she was the last artist to sell a million in a week, when 2012’s transitional country-to-pop crossover album Red moved 1.208 million in its debut.

The first artist to score a trio of platinum-weekers: Selling a million albums in a week is an extraordinary feat. Doing it twice is elite; Backstreet Boys, ’N Sync, and Eminem each scored two. Three times is madness, and only Swift has done it: Her last two albums—2010’s Speak Now (1.047 million) and the aforementioned Red—debuted to seven figures. Now, with 1989, Taylor scores an improbable trifecta—and by the way, her opening sales actually increased slightly on each of the three albums.

Instantly the year’s second-best seller, and the top seller by a single artist: All year, from January through October, only one album had sold more than a million copies cumulatively—the unkillable Frozen soundtrack (3.2 million sold in calendar 2014). The next two top-selling albums, Beyoncé and Lorde’s Pure Heroine, have sold just under 800,000 apiece in 2014. (Each sold additional copies in 2013.) With over a million sold in just its first week, Swift’s 1989 toppled both those ladies’ albums (by roughly half a million!) and now ranks second for the year, behind only the various-artists Disney soundtrack.

Only 2014 release to sell a million—not just in a week, TOTAL: Here’s the thing about Frozen, Beyoncé, and Pure Heroine—they’re all 2013 releases still selling well in 2014. Among albums dropped since January, the best-seller to date is Coldplay’s spring release Ghost Stories, which has sold 740K. And that number is cumulative—Coldplay sold that much in 23 weeks. Put another way: Taylor’s album is platinum-level out of the box; no other disc released in 2014 has even crawled to platinum.

It’s these last stats that should blow your mind. It isn’t just that Taylor managed to keep her platinum-weeker streak going. It isn’t just that she defied early predictions for 1989’s sales, beating the odds in a terrible climate for albums. Or that her risky and painstaking effort to cross fully from country to pop succeeded beyond anyone’s imaginings. It’s that her album is so, so much larger than anything else out there—she is the exception to every rule, standing astride the music business like a colossus.

It’s hard to fathom how Swift’s accomplishment is even possible. If no album all year can sell a million copies cumulatively, how does one album do it in a week? Much of this week’s chatter has focused on the non-availability of 1989 at Spotify; in the last couple of days (after the album’s first week on sale), Swift deepened her feud with the streaming service by pulling her back catalog, too—because she can. That lack of streaming availability is certainly a factor, and in the Spotify era it might spell the difference between breaking a million like Swift did and falling just shy, as Justin Timberlake did with his Spotify-available 2013 album The 20/20 Experience. As for the music itself, critics and culture-watchers trying to explain 1989’s improbable reception are crediting Swift’s unique pop persona—her deft positioning as charmingly awkward white girl who stands apart from modern black-derived pop and comes off as every young person’s bestie.

There’s truth to all of these Swift-specific theories. But the success of 1989 is part of a larger cultural narrative. Back in 2006, Chris Anderson, then the editor-in-chief of Wired, published a book called The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More. The title refers to the right end of a graph showing sales totals for, say, books or DVDs or albums. But in the music industry in 2014, a graph of album sales would not be a gentle slope curving gradually downward from mass-market to niche. These days, that curve would look more like a right angle. The blockbusters aren’t getting smaller. Everyone else is.

This becomes clear if you look at Taylor’s hat trick of blockbuster debuts in the context of recent pop music history. Listed below are the top sales weeks of the last two decades on the Billboard album chart. All of these 21 albums exceeded 950,000 in sales in a week—so they’re all platinum-weekers or very, very close to that. I’ve organized the albums chronologically and grouped them by year; in parentheses are the album’s sales in that blockbuster week and the Billboard issue date.

What patterns can we draw from this list? Well, clearly, no period in music-biz history will ever top the turn of the millennium. (Or should I say the turns of the Millennium?) From late 1998, when country megastar Garth Brooks scored the first million-sales debut in SoundScan history, to early 2002, when Eminem scored his second straight platinum-weeker, 10 albums pulled it off—an average of roughly one every four months. The year 2000, which was peak boy band, was particularly insane, as MTV TRL favorites ’N Sync and Backstreet and Britney and Eminem and Limp Bizkit (the boy band of aggro-rock) each debuted to 1.3 million or more. (You can even count a sixth album for 2000, by that erstwhile boy band the Beatles—their platinum-weeker, logged in a January 2001 issue of Billboard, actually reflected sales from Christmas week 2000.)

Of course, during that frothy period, virtually everything was selling well. In the industry’s peak year, 2000, the median No. 1 debut sales number was 543,000 copies (achieved by R. Kelly’s TP-2.com). No album debuted on top that year with fewer copies than Radiohead’s Kid A, with 207,000. In all, 17 albums debuted on top that year, selling a combined 13 million copies in their opening weeks. The year’s biggest debut, ’N Sync’s mind-blowing 2.4 million for No Strings Attached—still the all-time one-week sales record—was three times the year’s average for a No. 1 debut.

Now consider 2014. We’ve had 28 albums debut on top this year, selling just 5.7 million opening-week copies combined. Among these 28 No. 1 albums, the median debut sales number, achieved by the Black Keys’ Turn Blue, is 164,000—less than one-third the 2000 median, and well below the lowest No. 1 debut that year. This year’s blockbuster sales week by Taylor is also lower than 2000’s blockbuster, the ’N Sync album—but it’s over half the size of ’N Sync’s, a much smaller drop than the median. Most telling, though: Taylor’s debut is six times the average of all No. 1 debuters. The gap between her and the rest is twice the gap that existed between ’N Sync and their less successful peers back in 2000.

In short, in 2000, the Syncers were the tallest kids in a healthy class. In 2014? Taylor Swift, meet Jonathan Swift: She’s Gulliver compared with her Lilliputian competition. (One might call her sales Brobdingnagian.)

But there’s another lesson here. Look at that chronological list of platinum-weekers again. Taylor is exceptional, sure, but she’s not alone. If sales across the industry have been getting increasingly horrific in the last decade-plus, why do we still see at least one platinum-weeker, or one just shy, basically every year? Since 2003, the only yearlong gaps have been in 2006 and 2009. Every other year, we either saw an album score a million-plus debut or come within a sneeze of it.

Let’s talk about one of those sneezers for a minute, Timberlake’s 2013 smash The 20/20 Experience. His 968,000-album opening just missed the platinum-week mark, but that tally was a major victory for JT, coming off a seven-year hiatus from recording—as with Swift this year, early 2013 forecasts had him selling half to two-thirds of that number. And Timberlake’s final tally for his debut week happened with one hand tied behind his back: His album was on Spotify from the get-go. In the end, 20/20 not only had the biggest debut of the year; with total sales of nearly 2.5 million, it was the only 2013 album to sell beyond double platinum—no other album that year came close. Timberlake in 2013 looks an awful lot like Swift in 2010, 2012, or 2014—utterly dominant and playing not just in a different ballpark but a different sport.

The differences between the platinum-weekers of the prior half-decade and the rest of the field are not as stark as Swift’s and Timberlake’s, but they are in an elite echelon. In 2011 the top album was by Adele, who won the ground game with her nice-and-steady blockbuster 21 (a now-legendary seller that debuted to a comparatively modest 352K), but there were also two big openers: Lady Gaga’s Born This Way kicked off with a platinum week, and Lil Wayne came close with Tha Carter IV. By year’s end, both of the latter two albums roughly doubled their initial sales and went double platinum, while every album below them struggled to cross the low-seven-figure mark in total sales. (In case you’re tempted to keep blaming streaming for the other albums’ poor performance, keep in mind that these 2011 feats largely occurred before the advent of Spotify in the States.) Going further back, Wayne scored an actual platinum-weeker in 2008 with Tha Carter III; by year’s end, his was the only album to reach triple platinum.

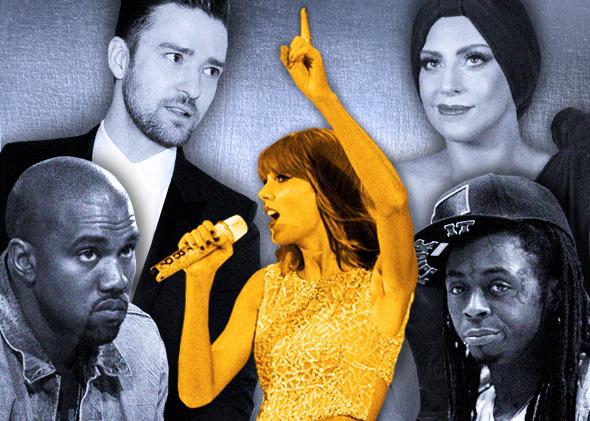

Basically, in the postmillennial, digital-first music business, you can divide artists into a small handful of elite megablockbuster acts and the 99 percent. And this is fundamentally different from the music world of the ’80s and ’90s. The Michael Jackson of Thriller may have been in a league of his own, but the ’80s acts just a half-tier below him—Bruce Springsteen, Madonna, Prince, Whitney Houston, Michael’s sister Janet, George Michael—were minting tens of millions in sales, and medium-tier acts like REO Speedwagon or Mötley Crüe did fine. In the ’90s, the album chart was dominated overall by Garth Brooks and Mariah Carey, but dozens of other artists were genuinely competing with them, dropping 5- and 10-million-sellers, from Pearl Jam to TLC to the Spice Girls. What we have now, on the other hand, is an extreme case of haves and have-nots. Swift may be quite a bit bigger than Lil Wayne, Justin Timberlake, and Lady Gaga. But really, when it comes to chart performance, this small handful of artists (plus consistent chart-toppers like Jay-Z and Beyoncé) is hobnobbing together in a very exclusive luxury box behind home plate while every other act is squinting from the bleachers.

Or if you don’t like baseball metaphors, consider football—and television. DVRs and online streaming have decimated TV ratings for the last decade; top-rated series of today like Modern Family and The Big Bang Theory wouldn’t even make the Top 50 in the age of Seinfeld and ER. And yet somehow the NFL keeps commanding ever-larger TV audiences for its live games. This year’s Super Bowl ranked as the most watched television program in U.S. history. It beat the ratings record set two years earlier by … the Super Bowl. And that 2012 game was the third time in three years it topped itself for the all-time record. The gap between live events, like the Super Bowl and the Oscars, and everything else on television is too large to even consider them the same kind of televisual entertainment at this point. In TV ratings as in music, it isn’t just winner-take-all. It’s winner-moves-to-a-private-island-and-secedes.

With her three-album streak of platinum-weekers, Taylor is clearly the Super Bowl of pop. (I suppose this makes Justin the Oscars of pop: elite, not quite as high-rated, very well-dressed.) Like Slate’s own Carl Wilson, you may well be enjoying 1989 as a sturdy, shimmering pop album that showcases Swift’s songwriting savvy. You may even be enjoying it more than new albums by fellow pop stars like Ariana Grande—I know I am—but are you enjoying it seven and a half times as much? Does Swift’s shrewdness, her skill, her singular persona warrant this different-class status?

Unlike some observers, I enjoy Taylor Swift enough that I wouldn’t propose taking up pitchforks against her. But make no mistake: Like our nation’s economy, popular music in the 2010s has an unmistakable class of 1 percenters, and Swift is its queen. A queen who pens op-eds for the Wall Street Journal and, I gather, recently moved just a few blocks away from Zuccotti Park.

Correction, Nov. 6, 2014: A chart with this article originally displayed the cover of the Backstreet Boys’ This Is Us instead of Millennium.

Content retrieved from: https://slate.com/culture/2014/11/taylor-swifts-1989-sales-top-1-million-copies-heres-what-that-says-about-pop-music-today.html.