100 & Single: What Billboard’s Rule Changes Mean For The Britney, Michael And Gaga Albums You Bought

When you go see a movie at a Saturday half-price matinee, should it count toward that weekend’s box office? You paid less than the guy who saw the movie Friday night. Does that mean your viewing shouldn’t count?

What about if you see an old movie at a revival house: Should that count toward the box office? I don’t just mean a big, nationwide rerelease like this year’s The Lion Kingin 3D. If enough people pay to see a restored print of Blade Runner, should it make the lower rungs of the box-office chart? What if that showing of Blade Runner was only playing at one theater, like the Ziegfeld in New York or Graumann’s Chinese in Hollywood? Should that count?

These questions probably seem like no-brainers. Sure, count it all, you’re saying. What’s the big deal? Maybe the matinee-priced movie should count half as much as the full-price, but otherwise no one would object to all movies at all theaters competing for the weekend title. In fact, that’s exactly how box-office tallying works. If it screens somewhere open to the public, it’s counted and charted.

Switch the medium from movies to music, however, and answering these questions becomes a matter of hot debate.

Another salvo in that debate landed in the pages of Billboard last week. On the Billboard 200 album chart, the big arrival is by indie rapper Mac Miller. His Blue Slide Park is the first chart-topping debut by a non-major-label act in 16 years, since Tha Dogg Pound’s Dogg Food in 1995.

But for industryites and chart-watchers, the more notable news is a rule change that’s got nothing to do with Miller and everything to do with a six-month-old Lady Gaga album. The magazine picked this week to announce the change, as its “chart year”—which runs from December 1 to November 30—draws to a close. (I hate the chart-year quirk, but that’s a debate for another day.)

Starting with the 2012 chart year, any album sold below $3.49 in its first month of release will not be tallied by Nielsen Soundscan for Billboard‘s charts. The same goes for a song sold below 39 cents. Such cheapo purchases won’t even get partial credit, like a movie matinee does—if you paid rock-bottom price for the recording, it won’t count for the charts at all.

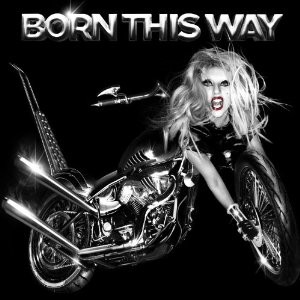

This rule is a direct response to Gaga’s last album, Born This Way, which topped the Billboard 200 in May under a cloud. For two days during the tracking week, digital retailer Amazon—unilaterally, and independently of Gaga or her label Interscope—priced MP3 downloads of the album at 99 cents. That’s cheaper than the normal price for a single, let alone a 14-track album. Smelling a bargain, some 440,000 folks bought Born during those two days at Amazon, which was promoting its new Cloud Drive music service.

If those fire-sale purchases distorted chart history at all, the damage was minor. The Gaga disc sold another 660,000 copies at higher-priced retailers that week; even if the new rule had been in effect then, Born would have been No. 1 handily, with a total more than four times higher than any other album.

But Born‘s splashy debut set a couple of other chart records, which are now regarded as dubious. Its official debut-week tally, 1.108 million copies, is 2011’s biggest; and it made Born one of only 17 “million-weekers” in chart history. Take away the cheapo Amazon sales, and those accolades disappear.

On various online forums, I’ve spent much of the last six months defending both Billboard for counting the Amazon sales and Gaga for earning a 2011 chart record. There’s been some Internet chatter that Gaga somehow gamed the system—ridiculous, given that Amazon, on its own, priced the album as a loss-leader, and paid Interscope full wholesale price (around $7) for each 99-cent sale. Some of the craziest accusations, that Billboard and Gaga were in cahoots to inflate her total, were tweeted by hardcore Britney Spears fans, for reasons that I’ll explain in a moment.

It’s fair to say that a large portion of the people who bought Gaga’s album for 99 cents wouldn’t have bought it otherwise. But it’s unfair to think that all 440,000 of those sales would have disappeared in the absence of a promotion. That’s how sales by retailers work—they pull in numerous new buyers as well as a large group of people who would have bought the product in question anyway. It’s safe to guess that tens of thousands of those cheapskate buyers would have bought Born This Way at a higher price. We’ll never know.

In any case, Billboard made the right call in counting the Amazon sales, because they’d never had a rule against lowball album pricing before. It would have been unfair to punish Gaga and her label for a sale that wasn’t their idea. Even if the sale was secretly Interscope’s doing, whoever thought up the 99-cent promotion to turbo-boost album sales was merely playing by the rules in effect at the time.

Those aren’t the rules anymore. It’s clear the Gaga kerfuffle forced the magazine to confront an issue they’d just as soon leave to market forces. In his commentary explaining the rule change, Billboard editor Bill Werde walks us through the chart group’s thinking: “Ultimately, what swayed us to make a rule change now—removed from any pressure connected to any particular album—was the fact that we wouldn’t want an album that sold for one penny to count on our charts. Our charts are meant to indicate consumer intent. And once you accept that you don’t want to count penny albums, the only remaining question is simply where a threshold should be.”

Breaking down Werde’s commentary, the two issues in making a big chart rule change are intent and timing. Billboard has had problems with both before.

Back in 2004, Prince came up with the novel idea of giving away his album Musicology to anyone buying a ticket to his concert tour. In a move they came to regret, Billboard counted all of these copies for the album chart—thousands of extra copies per week. Musicology rode the chart longer than any Prince album had in more than a decade, many of those weeks in the Top 10, which raised the hackles of competing record labels. Realizing that a giveaway album—even one attached to the price of a concert ticket—is not the same as an album somebody took the time to purchase, Billboard announced in the middle of 2004 that no other album would be tallied this way in the future. It was a fairly easy call in terms of consumer intent, but Billboard‘s editors botched the timing a bit.

That kerfuffle was a mere appetizer for much bigger rule changes the magazine enacted later in the decade. Two of these, made just in the last four years, have had a profound impact on the album chart. And the way they were timed proved seriously controversial—so much that those Britney fans are still angry.

In the midst of Spears’ 2007 meltdown, she dropped her fifth studio album, Blackout. Despite her troubles the disc sold well—not at the level of Brit’s early-2000s heyday, but fans (and the morbidly curious) purchased a respectable 290,000 copies. It was poised to become Spears’s fifth consecutive No. 1 album.

That same week, long-dormant rock stalwarts the Eagles released a Wal-Mart-exclusive comeback album, Long Road Out of Eden. It sold 711,000 copies in its debut week, more than twice the number of copies Spears’s album did. But it wasn’t supposed to chart at all.

As of 2007, Billboard 200 rules stated that albums had to be available to all retailers to be eligible to chart. The rule was only a few years old, but it had held back dozens of albums from the big chart; Billboard had instituted the rule in an attempt to support the music-retailer community, which complained loudly of the increasing number of discs labels and artists sold exclusively at Target, Best Buy or Starbucks. The biggest album-seller of all was Wal-Mart, which not only sold exclusive albums by blockbuster acts ranging from Garth Brooks to Kiss, but wouldn’t even report these albums’ sales to Soundscan. The single-retailer rule was relatively uncontroversial, because most weeks these exclusives didn’t sell well enough that their inclusion on the chart would have made a major dent.

The Eagles album, however, sold so outrageously well that Wal-Mart announced the 711,000 figure in a press release. The retailer was also proud enough of the accomplishment that they agreed, at the last minute, to provide Soundscan with sales data on a Wal-Mart exclusive for the first time. In light of all this, Billboard—not wanting a “secret” best-seller to overshadow its industry bible of a chart—immediately reversed the single-retailer rule and allowed Long Road to appear on the Billboard 200.

Spears’s album landed at No. 2, the only studio album of her career not to top the chart. Britney stans were furious, and as Spears has gone on to mount her career comeback and hit No. 1 with subsequent albums Circus and Femme Fatale, they have only gotten madder at Billboard for the blot on her otherwise spotless chart record. They will never forget: earlier this year, Brit fans were the ones crying loudest for Billboard to discount the 99-cent Gaga sales, noting the magazine’s perceived pro-Gaga bias. (Seriously.)

It’s understandable that Spears fans would feel aggrieved by the 2007 switcheroo, but Billboard made the right call. It would have been silly to pretend the Eagles’ album wasn’t the country’s best-seller that week.

Sure, it was unusual to make a big rule change in the middle of a chart year (though not unprecedented; the single biggest change in album-chart history, the epochal switch to Soundscan data, happened in May 1991, smack-dab in the middle of the year). When in doubt, I always err on the side of more or better data, not less.

That brings us to Billboard‘s other big album-chart reversal, at the end of the 2009 chart year. This one regarded “catalog” (i.e., old) albums, and it was an even bigger deal. You might not have known that, for almost 20 years, Billboard scrubbed dozens of old albums from the chart, no matter how well they sold.

The catalog rule was set in the early ’90s, when the advent of accurate counting made possible by Soundscan made it painfully clear that Led Zeppelin IV and Dark Side of the Moon would sell well enough to crowd the album chart week after week, bumping decent-selling new albums by fledgling acts. So, starting in 1991, albums that fell below the top half of the chart and were more than two years old were permanently removed from the chart. This even included Christmas albums that would sell well for a couple of months each year: no return appearances by Bing Crosby, Vince Guaraldi or Mannheim Steamroller.

Again, as with the single-retailer rule, most of the time this edict wasn’t controversial. Catalog perennials like Bob Marley’s Legend and Journey’s Greatest Hits would sell thousands of copies a week, but rarely enough to threaten current hits. Leaving them off the big chart pleased the industry, by making space toward the bottom of the list for up-and-coming acts, and it didn’t bother very many chart-watchers.

That was before the June 2009 death of Michael Jackson. With no current Jackson albums in stores the week he died, piles of his old discs began selling like crazy. For six weeks that summer, his 2003 hits collection Number Ones was the best-selling album in America, and his 1982 classic Thriller was among the 10 best-selling. But you wouldn’t know that by looking at the Billboard 200, where both albums were ineligible due to the catalog rule.

Even as Jackson’s sales piled up through July and August of that year, the magazine’s editors—remembering the Eagles/Spears commotion—resisted the urge to change the catalog rule immediately and grant Jackson a No. 1 album. Finally, in late November, after the posthumous Jacko-mania had largely passed, Billboard announced that it was killing the catalog rule, effective with the 2010 chart year.

To an extent, the wait was understandable, because including old albums has such an outsize effect on the makeup of the Billboard 200. This week, for example, with the Christmas season approaching and a slew of old titles selling well, catalog titles make up more than one-fourth of the chart—54 titles, to be exact, that wouldn’t have been there under pre-2010 rules, that could have gone to newer acts and newer albums.

As a chart-watcher, however, I still come down in favor of more complete data, not less. It’s a distortion of the record not to include albums just because they’re old. This week, I’m happy to know not only that Florence + the Machine’s new album, Ceremonials, was the 12th-biggest seller in the country, but also that Florence’s catalog disc Lungs ranked 84th, and sold better than new albums by Vince Gill and Mindless Behavior. Earlier this year, after a Glee episode revolving around the music of Fleetwood Mac, we got to see their classic Rumours re-debut on the big chart, just below the Top 10.

I’ve spoken with industry folk who hate that there’s less room on the big chart now for newer albums. But that doesn’t bother most chart fans I know. For us, the controversy is all about the timing of the rule changes. In 2007, the editors changed the single-retailer rule in the middle of a chart year, and it had an outsize effect on Britney’s album. It was messy, but probably necessary. In 2009, they changed the rule months after the change could have helped the late Jackson.

I would argue that, if they were going to fix the first rule immediately, they should have fixed the second rule immediately, too—in the summer of 2009, the minute they realized Jackson’s old hits disc was going to outsell every album on the chart. Waiting until December was pointless.

For his part, Billboard editor Bill Werde feels differently. In several commentaries this year, Werde has said that he would not have made the Eagles-related insta-change in 2007—but he wasn’t in charge of chart policy then. He was in charge by 2009, when Billboard chose to wait on the catalog rule, for a time when it wouldn’t affect Jackson; and he similarly pushed to wait this year on the pricing rule so it wouldn’t affect Lady Gaga.

It should be noted that the latest, Gaga-fueled change, regarding album pricing, is a different animal from the single-retailer change of 2007 and the catalog change of 2009. This is a new rule, on a subject that’s never come up before, rather than the elimination of an old rule.

I’m curious to see what happens the next time a retailer chooses to price a big album at a loss—will the label beg them to price it above $3.49 so they don’t lose chart credit? Fortunately for you bargain-hunters out there, the new Billboard rule won’t affect the most common sale prices. Even before the Gaga experiment, Amazon was the target of complaints for its frequent lowball MP3 pricing; in the summer of 2010, the Arcade Fire scored their first No. 1 album thanks in no small part to Amazon pricing The Suburbs at $3.99. But that price will continue to be chart-legal.

When it comes to the latest rule change, Werde and I are on the same page. Introducing a totally new, unprecedented rule immediately, in May, would have been unfair to Gaga and Interscope.

I feel differently, however, about eliminating old rules that are made pointless by changing market conditions. Kill them now, regardless of the time of year, I say. The Eagles—believe me, this is not Don Henley fandom talking—deserved their No. 1 album in 2007, and so did Michael Jackson in 2009. But only one of those acts got its just desserts.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I see BAM Rose Cinemas in my neighborhood is screening a print of The Blues Brothers tonight. I doubt enough of my fellow Brooklynites will show up to pose any threat to Breaking Dawn, Part One at the box office—but it’s nice to know my ticket will be counted.

Content retrieved from: https://www.villagevoice.com/2011/11/22/100-single-what-billboards-rule-changes-mean-for-the-britney-michael-and-gaga-albums-you-bought/