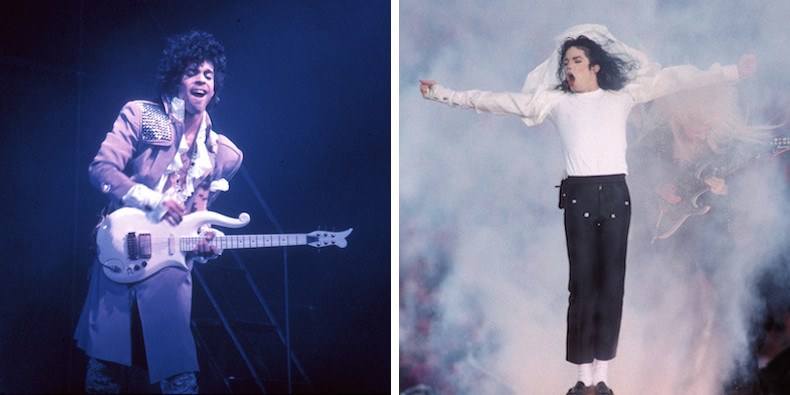

Prince and Michael Jackson: Still Competing, Posthumously, on the Charts

Since his death three weeks ago, Prince has been lodged in the upper reaches of the Billboard charts, as hundreds of thousands of Americans have acquired his music—in many cases, for the first time. Prince’s near-total refusal to allow his music on streaming sites of any kind—no Spotify or other on-demand audio sites except Tidal, vigilant takedowns of his material on YouTube during his lifetime—meant that most mourners wishing to experience or re-experience Prince’s material had to buy it.

You could see the results all over Billboard’s two flagship charts, the Billboard 200 album chart and the Hot 100 song chart. At our peak moment of national grief, Prince held down literally half of the Top 10 on the album chart. And in that same week, Prince lodged two singles, “Purple Rain” and “When Doves Cry,” in the Top 10 of the Hot 100—the first time he’d had that many tunes in the winner’s circle since his 1984 peak. A chart performance like that is rare among living artists, let alone the deceased. This week, for example, Drake set a new record for most simultaneous Hot 100 singles with tracks from his new album VIEWS; but counting only songs on which the Toronto rapper takes lead credit, he has one song in the Top 10 (the chart-topper “One Dance”) and a bunch of songs ranked at No. 21 or below. Prince, with his pair of lead-credit Top 10s the week before, had even Drake beat.

That last sentence should make His Royal Badness smile from the great beyond. Prince loved besting the competition—be it Super Bowl halftime performers or fellow Rock Hall inductees or rivals in a pickup basketball game. Even in death, Prince would love to know he slayed the competition. Accordingly, it’s hard to find any pop eminence who held quite this sway over the Billboard charts… well, at least since 2009, when Prince’s lifelong competitor Michael Jackson died under equally shocking, premature circumstances. The postmortem parallels between them on the charts are indeed spooky. In the last seven years, Billboard rules and the music business have changed enough to make apples-to-apples comparisons between the two superstars’ sales feats challenging. But a clear-eyed analysis shows they really were held in similar regard by the public. Arguably, Prince even has Michael to thank for why he’s charting this well, with so many albums and singles, at all.

Of course, posthumous sales boosts are not limited to Mr. Nelson or Mr. Jackson. Broadly speaking, any famous musician who dies—particularly when the death is sudden or unexpected—will see a bump on the charts, as sales are boosted by the heartfelt mourner and the morbidly curious alike.

This dates back decades: John Lennon’s December 1980 murder sent his virtually brand-new album with Yoko Ono, Double Fantasy, hurtling to the top of the charts, where it stayed for two months. Kurt Cobain’s April 1994 death lifted In Utero, Nirvana’s roughly six-month-old album, back into the Top 20, and all of the group’s albums to higher positions; for a brief time Bleach was the nation’s top catalog seller. Selena’s murder in March 1995 brought several of her Spanish-language albums onto the U.S. charts for the first time and, four months later, spurred her English-language debut Dreaming of You to debut at No. 1—a bittersweet crossover breakthrough. The shootings of Tupac Shakur in September 1996 and Christopher “Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace in March 1997 spurred their just-recorded studio projects—the former’s Makaveli album and the latter’s Life After Death—to career-best debuts when each was released just weeks after their respective deaths. Johnny Cash’s passing in September 2003 sent his 10-month-old American IV album, containing his aching cover of Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt,” hurtling back into the Top 40, and his 16 Biggest Hits collection became the best-selling catalog title for most of 2003’s remaining months. Just this year, David Bowie scored the first U.S. No. 1 album of his career—yes, ever—when his swan song Blackstar debuted on top the week after his death in January.

What makes Prince’s postmortem chart performance special, however, is its dominance and breadth. As we see in the above examples, it’s not that unusual for a deceased artist to hit No. 1, nor is it odd for multiple titles from the act’s back catalog to sell well. It’s not even unprecedented for old albums to reach new chart peaks, like Nirvana’s Bleach or Selena’s Spanish catalog did. What is exceptional is that Prince is doing all three—topping the chart, with multiple titles, while hitting new peaks.

We now have three weeks of Prince’s afterlife sales to track. His April 21th death happened on a Thursday—the last day of the tracking week Nielsen and Billboard use to compile the charts. Remarkably, with less than one full day of posthumous sales, The Very Best of Prince topped the Billboard 200 chart—for the whole week—and Purple Rain came in at No. 2.

The following week, with sales taken from the first full seven days after his death, Prince dominated the Billboard 200, especially the Top 10: Very Best of Prince, Purple Rain, The Hits/The B-Sides, Ultimate Prince, and 1999 made Nos. 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7, respectively; that’s five of the nation’s top seven albums. (If Prince hadn’t died the week Beyoncé happened to drop Lemonade, which naturally debuted at No. 1, he’d have had five of the top six.) During these first two weeks, all his hits compilations reached new chart peaks—and so did 1999. In its original chart run, that 1982 double-LP, which spawned the hits “Little Red Corvette,” “Delirious” and the title track, peaked at No. 9; this time it hit No. 7.

This week, the third since Prince’s death, finds his sales beginning to cool, but he is still all over the Billboard 200. Purple Rain and Very Best remain in the Top 10, 1999 is in the Top 20, and four more discs are in the Top 60. Below the Top 100 we even find such curios as HITnRUN: Phase One, Around the World in a Day, and Art Official Age selling in the thousands, suggesting a new generation is acquainting itself with the farther corners of the man’s oeuvre.

The only deceased music star to come near, or top, this level of posthumous chart dominance is Michael Jackson. Following his June 25, 2009, death, Jackson was basically the top-selling artist in America for the rest of the summer. Like Prince, Jackson died in the middle of a Nielsen tracking week but wound up with the week’s top-selling album anyway, based on just three days of posthumous sales. Like Prince, Jackson did it with a greatest-hits album: Number Ones shot to the top, followed immediately by The Essential Michael Jackson and, in third place, the perennial Thriller. In the second chart week after Jackson’s death—a full seven-day period—Michael again held three of the 10 best-sellers and a total of six of the top 40. In his third week, Jackson utterly commanded the charts, holding six of the 10 top-selling albums—Number Ones, Thriller, Essential, Off the Wall, Bad, and Dangerous at Nos. 1, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 9, respectively—and, including Jackson 5 albums, 10 of the top 40 (final studio album Invincible just missed at No. 41). Like Prince, Michael’s greatest-hits collections all achieved new chart peaks, although none of his studio albums beat their original chart ranks a la Prince’s 1999.

One interesting wrinkle, which complicates Michael–Prince comparisons: None of Jackson’s albums appeared on the Billboard 200 album chart in 2009. Back then, Billboard had rules that kept old titles (“catalog” in industry parlance) off the flagship album chart. This disadvantaged Jackson when he died—and, ironically, his death had a large hand in changing the rules in Prince’s favor.

Some brief history: The advent of the Soundscan Era on the charts in 1991—which brought accurate, computerized music sales-tallying to Billboard for the first time—revealed that dozens of classic rock and pop albums, from Dark Side of the Moon to Bob Marley’s Legend, were routinely among the weekly 200 best-sellers. (During the holiday season, dozens of old holiday titles like A Charlie Brown Christmas would hog the list, too.) Lest these oldies clog the chart week after week, Billboard appeased the industry in 1991 by shunting these old albums to a new, separate chart, Top Pop Catalog, which allowed more current titles on the big chart. Over the next decade, the Billboard 200 rules got even more complicated—in the early 2000s, the music-retail community compelled Billboard to also remove single-retailer titles like Walmart exclusives from the chart, too. To help keep everything straight, in 2003, the magazine launched a separate chart, Top Comprehensive Albums, that tracked everything: current and old, wide-release and exclusive. For six years, these two album charts—Billboard 200 and Comprehensive Albums—ran in parallel, in the magazine and online.

This is where Michael Jackson comes in—his summer 2009 chart feats were all on the Comprehensive Albums list, not the Billboard 200. Prior to his death, no catalog title had ever, in 18 years, outsold the No. 1 album on the Billboard 200. But for six weeks, Jackson’s Number Ones album did. (In the magazine, a hodgepodge of titles including the Black Eyed Peas’ The E.N.D. and Demi Lovato’s Here We Go Again were shown as No. 1 during these weeks—all of them lower-sellers than Michael.) This confused the media and frustrated chart-watchers, and by the end of the year, spurred in large part by Jackson’s feats, Billboard determined that the exclusionary album rules had become outmoded. In December 2009, Top Comprehensive Albums disappeared and effectively became the Billboard 200, as the magazine revoked all of the age and retailer limitations and allowed all titles to appear on the one big chart.

So in 2016, Prince looks more impressive than Jackson when you strictly compare Billboard 200 performance—because all of Prince’s old albums are now allowed to appear on the flagship chart, and Jackson’s catalog wasn’t seven years ago. For example, Prince’s five albums in the Top 10 two weeks ago is an all-time Billboard 200 record, even though for one week in ’09 Michael had six of the nation’s 10-best-sellers.

During this same seven-year interregnum, there was also a parallel rule change on the Hot 100 that allowed old songs to appear there—a change, oddly enough, prompted by another superstar’s death, Whitney Houston in 2012. Immediately after Michael’s death in 2009, his catalog of classic hits sold like gangbusters at digital retailers like iTunes; according to Billboard, fully one-third of the top 75 digital songs that week were Jackson songs. But none of them were eligible for the Hot 100, even though the Digital Songs chart showed Michael commanding six of the top 10 best-sellers. After 2012, old singles were permitted to appear on the Hot 100 if they accumulated enough points to make the Top 50. This advantaged Prince, too—the blockbuster digital sales of his songs on iTunes, combined with solid posthumous radio airplay, put the aforementioned pair of songs in the Top 10 and a total of eight songs in the Top 40, from “Kiss” to “I Would Die 4 U.”

So Prince’s chart achievements, amazing as they are, come with some asterisks when held against Jackson’s. In general, in must be said, Jackson’s posthumous sales outdistanced Prince’s. In 2009, Jackson’s Number Ones wound up spending six weeks as the best-selling album in America. This year, Prince’s Very Best had just one week and is unlikely to return to the top spot. In total, during the first three weeks encompassing and just after his death, Jackson shifted 2.3 million albums and 5.9 million digital tracks. During Prince’s corresponding three postmortem weeks, he moved 1.3 million albums and 3.9 million tracks.

On the other hand, the seven years between 2009 and 2016 have seen fairly radical change in the shape of the music industry, giving a leg up to Jackson. Album sales in general are down roughly 35% from 2009 through 2015. That alone could explain most of the 43% difference between Prince’s posthumous sales and Jackson’s. Spotify also didn’t exist in America when Jackson died in 2009. If streaming had been an option, a couple of million Americans might have purchased fewer Jackson singles and albums.

While Prince has no music on Spotify, the very existence of streaming over the last half-decade means many Americans are now out of the habit of owning music at all. Just in the last year, aggregate digital music consumption has surpassed physical purchase for the first time. Indeed, what made Prince’s posthumous sales pattern this year unique was that, given his anti-streaming stance, fans more or less were forced to buy his music. This surely helped him, but it is also easy to imagine many younger fans unaccustomed to music purchase either not bothering with Prince at all, or helping themselves to his music on YouTube as scores of his videos became unblocked after his death. (Tidal, for the record, is among the streaming services factored into the Hot 100 and Billboard 200 charts, but based on the data reported to Billboard, streaming did not play much of a role at all in earning Prince his high chartings.) All these X-factors make it hard to know exactly how to stack the late Prince’s performance against his ’80s crossover contemporary.

If there is an afterlife, one can picture the conversations going on right now between Prince and Michael Jackson—two musical geniuses, both born in 1958 and, thanks to prescription painkillers, both gone too soon. Maybe they’re reminiscing about their old battles back in the day: commiserating over those small-minded 1983 MTV programmers, comparing notes on their rivalrous night with James Brown, or burying the hatchet over “We Are the World.” Maybe Prince is finally humoring Michael by singing the opening line of “Bad.” And while they’re good-naturedly ribbing each other, maybe Prince is bragging about how he’s doing on the charts right now. “Hey, man, I changed the Billboard rules,” MJ could quip back, “so you owe me one for that.”