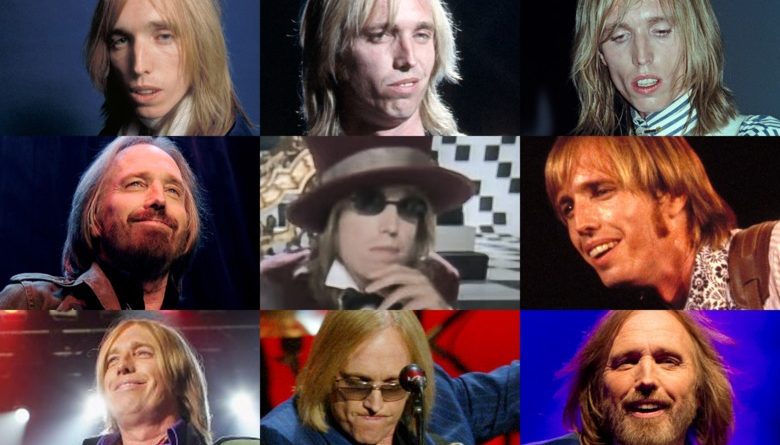

Tom Petty Was a Rock Chameleon

His career quietly spanned subgenres, from new wave to Southern to classic to grunge—anything that was rock ’n’ roll

The performance that is rightfully enshrined as the greatest in the history of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame features an incendiary Prince, shredding on George Harrison’s Beatles classic “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” while an all-star band looks on in wonder. Among those looking on and providing unflashy, steady backup in that March 2004 performance is one Thomas Earl Petty—Prince’s accompanist that night, but also a specific kind of peer.

Tom Petty was the only person standing onstage that night besides Prince who’d been inducted into the hall in his first year of eligibility. Performers become eligible for Rock Hall induction no earlier than 25 years after their first recording. Virtually all of that night’s inductees—Jackson Browne, the Dells, Bob Seger, Traffic, ZZ Top—had been eligible for the honor about a decade or more apiece before being belatedly let in. Even the late Harrison, a friend of Petty’s inducted that night for his post-Beatles work (and whose son Dhani was also playing on “Weeps”), was let in as a soloist a decade late and two years after his death. Rock Hall first-balloters, from Chuck Berry to Pearl Jam, form a very exclusive club: a few dozen performers so undeniable their contributions to the popular canon are like oxygen, universally beloved and easy to take for granted.

Petty—who flew into the great wide open Monday night at age 66, just days after completing a 40th-anniversary Heartbreakers tour—might have been the easiest of all. Like the gone-too-soon Prince, Petty was born in the ’50s and entered his prime recording years in the late ’70s, after the rock canon had begun to harden and calcify, a magpie who’d ingested the entire foundation of rock’s first two decades and sought to reinvent it for a generation coming of age after punk. As legendary as Prince’s virtuosity and versatility were, Petty was the quieter chameleon: variously described as classic, country, or heartland rock; claimed by both the American South and Southern California; briefly marketed as new wave; hugely successful on MTV and Top 40 radio, even in the dance-pop years; and scoring current-sounding hits deep into a ’90s grunge era that wasn’t hospitable to many of his peers. A gifted melodist and songwriter, Petty didn’t so much adapt to the times as assume his undeniable rock was built for all eras. Again and again, on the radio and the hit parade, he was proved right.

How universally appealing was the Gainesville, Florida, native’s economical pop? Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ first Top 40 hits were scored not in the United States but in England, where “Anything That’s Rock ’n’ Roll” (U.K. No. 36, 1977) and “American Girl” (U.K. No. 40, 1977) scraped the charts before any Petty single had so much as appeared in Billboard. (It is particularly bizarre that “American Girl” never made the Hot 100.) Watch the band mime “Anything” for German TV, and their trans-Atlantic appeal sharpens into focus—Petty and the Heartbreakers are a hybrid of American roots rock and the blazer-clad pub and mod rock then sweeping British pop. Squeeze’s Glenn Tilbrook would later reminisce about the band’s British telly appearances and their “punk energy.” When Petty finally broke on the American pop charts a few months later, it was with the minor hit “Breakdown” (No. 40, 1978), a slow-burn, keyboard-drenched rock cut with a smoldering R&B edge. It was soulful enough that, when playing it live, Petty would merge it into a medley with Ray Charles’ “Hit the Road Jack,” and two years later, Grace Jones turned it into credible pop reggae with the help of Petty, who wrote a third verse for her.

The industry’s attempts to present Petty’s gang as skinny-tie new wavers—Petty would later laugh about that misleading marketing—didn’t last long. After a sophomore LP went gold but generated no Top 40 hits (the crunching “I Need to Know” came up just shy, peaking at No. 41 in the summer of ’78), Petty joined forces with rising producer and future mogul Jimmy Iovine for 1979’s Damn the Torpedoes. Released after a yearlong battle with Petty’s own record label, the future triple-platinum classic remains the Heartbreakers’ biggest studio album as a band, and it plays like an instant greatest hits. Torpedoes spent seven weeks at No. 2 on the album chart (stuck behind Pink Floyd’s The Wall) and half its tracks were radio hits, including the fleet “Don’t Do Me Like That” (No. 10, 1980), the Heartbreakers’ biggest pop hit, and the tough-minded “Refugee” (No. 15, 1980), co-written with ace Heartbreakers guitarist Mike Campbell. The latter came packaged with a low-tech music video at a time when MTV still didn’t exist, but Petty’s timing would prove propitious, as the arrival of music television a year later made the blond, toothy, striking-looking frontman an early video star. On its very first day, MTV power-rotated Petty’s smash duet with Stevie Nicks, “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around” (No. 3, 1981)—a Petty song that Iovine poached for Nicks’ solo debut. And Petty and the Heartbreakers went into regular MTV rotation with their own hits “The Waiting” (No. 19, 1981) and “A Woman in Love” (No. 79, 1981).

As the chiming “The Waiting” reinforced—its 12-string Rickenbacker melody an obvious homage to the Byrds, whose leader Roger McGuinn was a hero to Petty, an obvious vocal model, and an eventual friend—Petty, barely into his 30s, was now writing insta-classic rock tunes on par with his influences. However, at a time when the charts were overflowing with synth-based New Romantic pop, Petty refused to settle into the predictable. The lead single from the Heartbreakers’ 1982 album Long After Dark, “You Got Lucky” (No. 20, 1983), was arranged by Petty around bandmate Benmont Tench’s synth stabs and promoted with a slick sci-fi music video echoing Mad Max. Similarly, 1985’s Southern Accents—an album meant to explore Petty’s relationship with his Confederate heritage, including the moving title track and “Rebels”—nonetheless led off with the scarcely Southern “Don’t Come Around Here No More” (No. 13, 1985), a psychedelic digital-rock track produced by Dave Stewart of Eurythmics, punctuated by electric sitar and cellos. Its trippy Alice in Wonderland music video was Petty’s most beloved MTV hit, nominated for a slew of Video Music Awards.

By the late ’80s, Petty wasn’t just emulating his American and British rock forefathers. He began playing with them. He and the Heartbreakers mounted a tour with Bob Dylan in 1986, and the next year Dylan, Petty, and Campbell co-wrote the snarky “Jammin’ Me” (No. 18, 1987), the lead single from the Heartbreakers’ album Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough). By now, Petty was a core artist for rock radio, and “Jammin’ Me” spent a month atop Billboard’s Album Rock chart. According to chart historian Joel Whitburn, by the end of the 20th century, Petty ranked as the second-biggest artist in the history of the mainstream rock chart, behind only Van Halen. By 1988, Petty was recording with Dylan as well as George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, and Roy Orbison as the Traveling Wilburys, whose debut album Volume One spent more than a year on the charts and went triple-platinum. The youngest Wilbury at 37, Petty followed the supergroup’s debut by co-writing the now-classic “You Got It” with Lynne and Orbison, for Orbison’s final album Mystery Girl—the song was even a posthumous Top 10 hit (No. 9, 1989) just months after Orbison’s death.

As Petty approached 40, he appeared to be settling into a fine dotage, arriving early at elder-statesman status, with approval from his rock icons, just as late-’80s popular culture was awash in boomer nostalgia. That’s when the truly improbable happened: Petty made his belated solo debut and became a bigger pop star than ever.

Produced by Petty’s fellow Wilbury Jeff Lynne, 1989’s Full Moon Fever—which despite the lack of “Heartbreakers” on the cover nonetheless featured half the band as players—was a quintuple-platinum smash. It went four singles deep at pop radio and seven tracks deep at rock radio, including the three Album Rock–topping, Top 40 pop hits “I Won’t Back Down” (No. 12, 1989), “Runnin’ Down a Dream” (No. 23, 1989), and “Free Fallin’ ” (No. 7, 1990). When “Fallin’ ” peaked on the Hot 100 in January 1990, it became Petty’s highest-charting hit (not counting the 1981 Stevie Nicks duet), and Petty found himself in a Top 10 surrounded by Michael Bolton, Technotronic, Jody Watley, and Skid Row. The album’s last radio hit, “Yer So Bad,” peaked in the Album Rock top five in the early summer of 1990, more than a year after Fever dropped.

Petty stuck with Lynne for one more album, reuniting the Heartbreakers for 1991’s double-platinum Into the Great Wide Open and its sparkling single “Learning to Fly” (No. 28, 1991). Though it wasn’t a big hit, the album’s title track (No. 92, 1991) sported a Julien Temple–directed video that starred Johnny Depp and Faye Dunaway and poked fun at MTV-era video-fueled fame. Even while affectionately biting the hand that fed him (at one point in the video, Depp’s “Eddie” rock-star character has MTV Moonman statues flung at him while floating in a swimming pool), Petty was beloved by the video channel and its Gen X audience. At the 1994 Video Music Awards, Petty took home MTV’s Video Vanguard award in commemoration of his years of surreal videos, as well as Best Male Video for the Kim Basinger–starring “Mary Jane’s Last Dance” (No. 14, 1994). By then, Petty—alongside such aging eminences as Neil Young—was being received by the grunge generation as an honorary contemporary. Performing “Mary Jane” at the VMAs that night, the jeans and Chuck Taylors–clad Petty looked remarkably comfortable and on trend. Perhaps that was because he was still scoring hits: Petty was weeks away from dropping his blissed-out stoner-rock jam “You Don’t Know How It Feels” (No. 13, 1995), which powered his second solo album Wildflowers to triple-platinum sales. Cementing the grunge connection, Petty invited Dave Grohl, who was still mourning the death of Nirvana bandmate Kurt Cobain and not yet a Foo Fighter, to join him for a November 1994 performance on Saturday Night Live, manning the kit for the Wildflowers rocker “Honey Bee.”

“You Don’t Know How It Feels” was Petty’s last Top 40 pop hit, but he wasn’t done influencing the hit parade—which he sometimes did accidentally. In 2001, the Strokes’ “Last Nite,” a No. 5 Modern Rock hit, was taken to task for borrowing its chord progression from Petty’s “American Girl,” and five years later, the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ even bigger hit “Dani California” (No. 6 pop, No. 1 Modern Rock) was accused of lifting chords from “Mary Jane’s Last Dance.” In both cases, the current songs and Petty’s chestnuts differed just enough that no money changed hands—but eight years later, British soul crooner Sam Smith wasn’t as lucky. His No. 2 smash “Stay With Me” seemed to lift its chorus melody wholesale from Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down,” and Petty and Lynne were added belatedly to its publishing credits. None of the cases saw a courtroom, and Petty was unfailingly magnanimous and fair-minded, saying of the Chili Peppers, “I seriously doubt that there is any negative intent there—and a lot of rock and roll songs sound alike” and calling Smith’s melody lift, “A musical accident, no more, no less.” Petty could afford to be kind to Smith—the same summer “Stay With Me” was peaking on the Hot 100, Petty was pulling off his last improbable career feat. Hypnotic Eye, the Heartbreakers’ 13th and final studio album, debuted atop the Billboard 200 in August 2014, fueled in part by a live-concert promotion that let fans buy the new album with their tickets. Yes, 34 years after Damn the Torpedoes got stuck behind Pink Floyd, Petty scored his first-ever No. 1 album at age 63.

Petty enjoyed these late-career feats for the same reason young acts stumbled into biting his tunes: The man wrote indelible melodies that sounded like they’d always been there. Those tunes are the reason I traveled from New York to Boston this summer to see a date on Petty and the Heartbreakers’ 40th-anniversary tour—my girlfriend, who’d loved Petty all her life but never seen him, called the show “a bucket-lister.” On the July night we saw him, Petty had seemingly never looked happier, thanking the crowd for giving him a career and grinning from ear to ear as his crack band closed the set with “American Girl” one more time. If you’d produced that many gems over that many years, floating above the vicissitudes of pop culture, you’d be pretty happy, too. He’d kept changing while staying true to his first hit, playing anything that’s rock ’n’ roll.

Content retrieved from: https://slate.com/arts/2017/10/tom-pettys-career-spanned-genres.html.