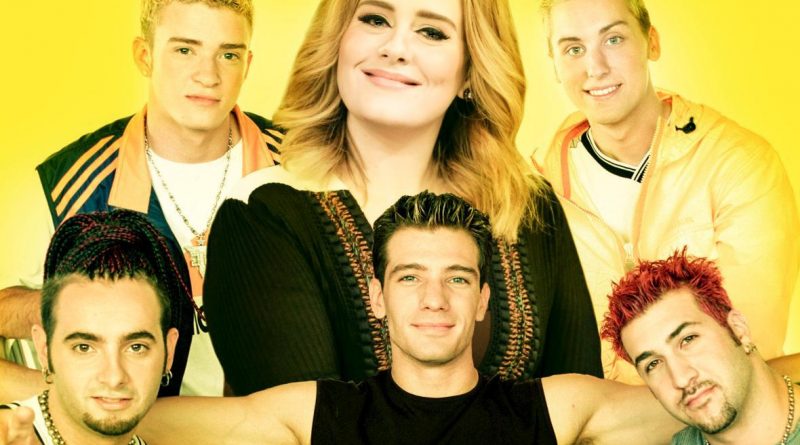

Why Is Adele’s 25 the Biggest-Opening Album of All Time? ’N Sync Might Give Us Some Clues.

Picture a young pop act selling a rare 10 million copies of an album: “diamond” status in America, a major career pinnacle. This is a remarkable feat, especially considering that the act originally launched in the shadow of another genre-defining artist. Our young act reached the diamond level the old-fashioned, solid-and-steady way: never selling a million copies in a week, routinely shifting a few hundred thousand at a time, and spinning off a raft of hit songs.

But when it comes time to follow the album up, things get complicated. Due to personal setbacks and the grinding machinery of fame, entering a recording studio becomes unthinkable. The act’s long break from recording only stokes fans’ hunger. As a stopgap, the act’s management and label issue more “product” to tide fans over—a holiday-timed disc containing warmed-over material, which sells a million anyway; a song from a movie soundtrack, which quickly cracks the Top 10 on the Billboard Hot 100. But what everybody wants is that follow-up album. Rumors, and potential release dates, come and go.

When the new album finally drops, roughly a year after it was expected and a dog’s age since the last one, the public’s pent-up demand boils over. The album debuts to record-setting numbers—not just a million-selling week but millions, plural—going instantly multiplatinum. This achievement, previously thought impossible, stuns the music-industrial complex. We knew the album would be huge, but not this huge.

So, what pop act am I describing: Adele, or ’N Sync?

All of the above could apply to either of them: the diamond-level sales for a prior album, and the progenitor acts they outdistanced (Backstreet Boys for ’N Sync, Amy Winehouse for Adele); the stopgap soundtrack hits and holiday releases; the long career pause (in ’N Sync’s case, over a fight with a corrupt manager and a label switch; for Adele, throat surgery, a baby, and a bout of career ennui); and finally, the explosive, expectation-shattering chart return.

In Adele’s case, truly explosive: Billboard and Nielsen report that, in just seven days, Adele sold 3.378 million copies of her third album, 25. (What was I saying a few weeks ago about this lady and grand entrances?) That brain-melting total—the biggest sales week in Nielsen SoundScan history, and quite possibly all of chart history, for a music album—not only surpassed but annihilated the seemingly indomitable benchmark of 2.416 million copies ’N Sync’s No Strings Attached sold in the spring of 2000. The list of all-time chart achievements in 25’s first week is a mile long: the first album to sell three million in a week in SoundScan history; the first album to outsell the rest of the Billboard 200 albums—combined; more compact discs sold (1.7 million CDs) than any album in 14 years, and the most digital albums sold (1.6 million downloads) in any week, ever.

In our new Adele-dominated world, it’s tempting to regard ’N Sync as cheesy roadkill—not unlike Flo Rida, the club-rapper whose digital-song record Adele demolished last month with her smash “Hello.” But I think laughing off ’N Sync, Adele’s precursor album-record-setter, would be a mistake. Because understanding how Americans of 2000 bought into the ’N Sync backstory might be the best way to make sense of what Adele just pulled off.

Honestly, it’s otherwise nearly inexplicable: How exactly did Adele’s 25—hell, any album in the year 2015—sell three million copies in a week, at a time when, supposedly, “no one buys music anymore?” (At this writing, 25 is already past four million sold thanks to Black Friday, which didn’t even fall during the album’s first week.) Last year at this time, I wrote about music’s one percent: the elite group of megastars who can open to a million copies and are in a completely different echelon from most hit acts, many of whom can’t even crawl to platinum status. If Taylor Swift—whose 1.3 million–selling debut a year ago with the album 1989 instantly gave her the top-selling album of 2014—is the one percent’s queen, Adele is its god. Her 25 became 2015’s top album instantly, one month before the end of the year. (Ironically, the album Adele topped for the 2015 title was 1989, which sold another 1.78 million copies this year.)

Put another way, if Taylor is the one percent, Adele is the 0.001 percent. Among the one-percenter traits I cited last year was these megastars’ ability to command the conversation among a fractured pop audience. This is doubly true for all-time record-setters like ’N Sync and Adele, who provide the public with a narrative that turns an album release into a capital-e Event. Swift, who issues new studio albums on a regular two-year schedule, expertly cultivates a persona that invites fans to be a member of her #squad. But the release of an event album like Adele’s 25 feels more a chapter in a long-running drama—what fans are buying into is not just the music and the talent, but the story.

Maybe that explanation for 25’s success seems a little broad and pat. But it’s no worse than some of the other half-baked theories (some of them my own!) I’ve been debating with my fellow pop-watchers over the last week. There’s some truth in all of these hypotheses, but they rely on a lot of music-business received wisdom, and none is entirely satisfying. Allow me to run down a few other Grand Unified Adele Theories and poke some holes in them.

The Old Folks Theory

This has been the snark theme of the week, and knowing how much your Mom loves Adele, you probably jumped to this conclusion yourself. It goes like this: people over 30 (or 40, or 50) still buy music; these oldsters all love Adele; so…duh, of course 25 set a record! Without a doubt, Adele’s eight-to-80 appeal is a major factor in 25’s huge sales. For adults who might buy only one album a year, Adele is the primary (perhaps only?) contemporary artist they follow. As Slate’s own Carl Wilson noted, Adele herself is actively courting this audience in her lyrics, and 25 has been ubiquitous in the places, from daytime TV to bookstores, where child-rearing, mortgage-having people congregate.

But the same was true a decade ago of Norah Jones—remember her?—the early-aughts lite-jazz queen of Starbucks CD racks and NPR pledge drives. As I noted on a recent Slate Culture Gabfest, Jones sold an Adele-size 10 million of her Grammy-dominating 2002 debut Come Away with Me, and when she returned in 2004, Feels Like Home debuted to over a million in first-week sales. But that sophomore disc by Jones topped out at only four million total, she never scored a serious radio hit, and her career since has been much more modest. Jones, in short, is a bit of a cautionary tale: Grayhead loyalty certainly helps an artist, but it can’t sustain a megablockbuster career. What made 21 so huge were big, dominant Top 40 hits—songs teens and twentysomethings were likely to hear—and 25 already has one such smash on it. Besides, news flash: When they are motivated, under-30s do still buy records, like Taylor Swift’s 1989—not to mention the album Adele knocks out of No. 1 this week, Justin Bieber’s Purpose, which debuted last week to a very respectable half-million in sales, likely to an army of millennials.

The Spotify Factor

This is the most reported, and I’d argue most overrated, theory for this album’s success. Literally the day before 25 arrived in stores, Adele and her labels XL and Columbia belatedly announced that it would not be available on streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music. That marked the third straight holiday season that the biggest superstar release was withheld from such services: 2013’s Beyoncé album was released only for digital purchase, not streaming; and in 2014, infamously, Taylor Swift both withheld 1989 and pulled her entire catalog from Spotify in open revolt against its business model. This year, numerous reporters have gravitated toward the unavailability of 25 on streaming services as the major factor in its blockbuster week. The New Yorker’s pop-and-tech writer and proud dad-rocker John Seabrook penned a rather spiteful commentary about his frustration at paying for Spotify and not being able to hear the new Adele album.

No one knows how many fewer copies 25 would have sold if some buyers could have streamed it instead. But all the evidence shows that Adele just tends to sell stuff, regardless of the ability to play that stuff for free. “Hello,” the album’s lead single, was made available on Spotify and YouTube from day one—and it broke the all-time digital singles-sales record anyway, by a huge margin. Moreover, in the weeks leading up to 25’s release, nearly a million people preordered the album on iTunes and other online services, even before the announcement about its non-streamability. By the way, one million is also the size of Adele’s final sales margin over the ’N Sync record—clearly, her label didn’t need to shut down streamers to handily reach their sales bar. Ultimately, I submit that streaming, or the lack thereof, is a footnote to the 25 story.

The AC/DC Rule

This is actually one of my pet theories, one I have used to explain the opening sales of many albums over the years. Named for a rock band who scored their first No. 1 with the album released after their most famous and best-selling album, the AC/DC Rule states that initial sales of an album are a referendum on the public’s feelings about the act’s prior album, not the current one. It also explains why so many follow-up albums are heavily front-loaded. They open to bigger numbers than the prior album ever saw in a week, but fall short over the long haul (the way, say, Lady Gaga’s huge-opening Born This Way ultimately sold about half as much as its slower-growing predecessor The Fame). Already, 25 looks like the AC/DC Rule on steroids: Adele’s 2011 album 21 was a megablockbuster but a more steady seller, never shifting a million albums all at once. Its highest-selling week, 730,000 copies, came in early 2012, one year into its run, right after it won the Album of the Year Grammy. Meanwhile, the total 25 racked up in its debut, 3.38 million, is four and a half times the size of 21’s peak—prime evidence of an AC/DC-style album that could open huge but eventually fall short of its slower-but-bigger-selling predecessor.

The thing is, though, 25 is starting to look like a follow-up that might not fall short. At its current rate, and even assuming a slowdown over the next month, the album could approach seven million in the U.S. by Christmas, a level 21 didn’t reach until it was a year old. Then, in 2016, assuming the album is able to generate just a couple more hit singles (the Max Martin–produced “Send My Love (To Your New Lover),” say, or the throbbing “Water Under the Bridge”), it is not inconceivable that 25 will wind up at the eight-figure sales level its predecessor reached. (For the record, ’N Sync’s No Strings Attached actually wound up surpassing the 10 million certification of its predecessor ’N Sync.) If 25 does winds up diamond like 21, it wouldn’t disprove my AC/DC Rule—25’s front-loaded first week already affirms it—but Adele’s ability to defy music-biz gravity over the long haul is remarkable.

“It’s the Music, Stupid”

Hardcore Adele fans may wonder why I’ve gotten this far without discussing the most essential thing about it: the tunes on the album. Would it kill us critics to say, simply, that the sales of 25 are a reward for Adele’s all-around high standards and unerring musical quality? Haven’t 3.4 million Americans voted with their dollars for a collection of songs from an artist they find reliably tasteful, whose voice they find awe-inspiring? They heard “Hello,” with that big-lunged, Adele-to-the-max chorus, and they pulled out their credit cards immediately.

Fair enough, but sales in the millions do not automatically vouch for an album’s quality. (Cracked Rear View, anyone? Human Clay?) As someone who generally loved 21, I do agree that Adele earned instant-purchase status from a large chunk of her loyal fanbase. But again, to reiterate my AC/DC Rule, that is a reflection of our feelings about the last album, not this one. As for 25, despite the requisite five-star review from Rolling Stone, the new disc has mostly received respectful, measured, not over-the-moon notices from critics. Not that critics matter much in a situation like this (they were only modestly positive about No Strings Attached, too). It’s now the public’s turn to evaluate 25—not just buying it but living with it for the next year. What critics and fans all agree about 25 is it’s a stately, smoldering, torch-song-heavy record. There’s no “Rolling in the Deep”–style banger on the album, nor are the album’s small handful of change-up tracks (“Send My Love,” “I Miss You”) terribly divergent from median Adele. In short, the first wave of 25 buyers were all about 21; the next wave will be more exposed to the new album, and they’ll need to be sold on the merits of its most insinuating songs.

Presented with all of the above theories, we have to conclude that Adele’s all-time sales week reflects many, many factors—maybe 3.4 million of them. Ignore anything you read this week that claims there’s one key element that singlehandedly explains the magnitude of her achievement.

Weirdly, I keep coming back to ’N Sync and that goofy 15-year-old album we will mostly forget about now that it’s a permanent runner-up. No Strings Attached is pretty easy to forget: a just-better-than-average teenpop album with nothing on it as classic as “I Want It That Way” or “…Baby One More Time”; its opening week was inflated by dot-com-era CD sales and millennial boy-band mania; its audience centered around a tight cohort of frenzied tweens and adolescents. Even if you regard Adele as “music for adults” the way ’N Sync was “music for kids,” 21 does inarguably have broader appeal. And 25 probably needed that bigger fanbase to beat ’N Sync in an era of vastly diminished music sales.

But what unifies Adele and ’N Sync are the compelling meta-stories that each told their audience. Once-a-generation album events like No Strings Attached and 25 are, by their nature, bespoke and unrepeatable: No artist goes into pop music hoping for a corrupt manager or throat problems. But record-breaking musical phenomena are about a narrative that’s larger than the music itself. The public feels invested in an artist when they have a rooting interest in them, whether they’re rooting against a competing boy band or a predatory music system, or rooting for a once-wronged woman who’s having the last laugh. Maybe you are worshipful of Adele, or maybe a little bored with her—either way, hers is a conversation everybody wants to join.

Content retrieved from: https://slate.com/culture/2015/12/adele-s-25-is-the-biggest-opening-album-of-all-time-n-sync-might-give-us-some-clues-as-to-why.html.