I Know You Got Soul: The Trouble With Billboard’s R&B/Hip-Hop Chart

Billboard’s R&B chart once reflected the tastes of the genre’s core fans, paving the way for countless legendary artists in the process. But now, slipshod methodology has rendered it a shell of its former self, replete with dubious racial consequences.

Content retrieved from: https://pitchfork.com/features/article/9378-i-know-you-got-soul-the-trouble-with-billboards-rbhip-hop-chart/

Here, for your consideration, is a Top 10 list published in Billboard magazine toward the end of last year, in the issue dated November 30, 2013:

- Eminem: “The Monster” [ft. Rihanna]

- Drake: “Hold On, We’re Going Home” [ft. Majid Jordan]

- Mike WiLL Made-It: “23” [ft. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa, and Juicy J]

- Jay Z: “Holy Grail” [ft. Justin Timberlake]

- Robin Thicke: “Blurred Lines” [ft. T.I. and Pharrell]

- YG: “My Hitta” [ft. Jeezy and Rich Homie Quan]

- Chris Brown: “Love More” [ft. Nicki Minaj]

- Macklemore & Ryan Lewis: “White Walls” [ft. ScHoolboy Q and Hollis]

- Eminem: “Rap God”

- Justin Timberlake: “TKO”

This list contains many of the year’s best-selling acts and, track-for-track, it looks like a fairly representative cross-section of 2013 pop. Except it’s not pop—at least, not according to the music-industry bible. This wasn’t the Top 10 of Billboard’s all-genre, authoritative Hot 100 chart. This was the Top 10 of the magazine’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart.

This Top 10 might make you cock an eyebrow if, like me, you define rhythm-and-blues and hip-hop as music largely, though not exclusively, conceived by, aimed at, and consumed by African-Americans. Obviously, whites can and do make excellent R&B and rap. The question is one of degree: In 2013, the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart was topped by a Caucasian person 44 out of 52 weeks—including 37 straight weeks, January to October, where it was topped by either hip-hop duo Macklmore & Ryan Lewis or blue-eyed soul singer Robin Thicke. Is it credible that a chart devoted to black-derived music should be dominated by white acts most of the time?

Ideally, any effective genre chart—be it R&B, Latin, country, even alt-rock—doesn’t just track a particular strain of music, which can be marked by ever-changing boundaries and ultimately impossible to define. It’s meant to track an audience. This is a subtle but vital difference. If an R&B chart tries to cover whatever might be termed R&B music, you get into the subjective, slippery business of determining what, or who, is “black enough” for the chart. That wouldn’t be appropriate for Billboard, a purportedly objective arbiter of the music business.

The goal is not to racially profile record buyers, either. Instead, by tracking the R&B and hip-hop audience—those who seek out black radio stations and maintain a steady diet of beats, rhymes, and soul, regardless of their own ethnic makeup—you get a much better read of the pulse of actual fans of the music: those who live and breathe it, week in, week out. That used to be what Billboard’s R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart did. It’s not what it does anymore.

Mind you, this isn’t the first time Billboard has run an R&B chart with so many white faces. For comparison, let’s go back 50 years. In the Billboard issue dated November 23, 1963, just under half of the Top 10 on the Hot R&B Singles chart was by white acts. And I mean really white. Hanging around that week’s top five were a pair of boy-girl duets with easy-listening pop vocals: “Deep Purple” by Nino Tempo and April Stevens and “I’m Leaving It Up to You” by Dale & Grace. Somewhat more authentic was rock legend Roy Orbison’s “Mean Woman Blues”—No. 8 R&B that week—a song obviously rooted in the 12-bar blues tradition, but one that had been recorded by a string of traditional rock’n’roll acts including Elvis Presley and Cliff Richard.

And what was No. 1 on the R&B chart back then? A song by white pop band Jimmy Gilmer & the Fireballs called “Sugar Shack”, a million-seller that also topped the Hot 100 and was Billboard’s No. 1 single of 1963. It’s a hokey song—and whatever its merits, the idea that “Sugar Shack” was a major hit among black audiences beggars belief. Gilmer’s hit topped an R&B Top 10 that also featured such black artists as Rufus Thomas (“Walking the Dog”), Sam Cooke (“Little Red Rooster”), and Ray Charles (“Busted”)—but none of those songs reached No. 1 like “Sugar Shack”.

The November 23, 1963, chart is interesting for reasons that have nothing to do with the coincidental assassination of President Kennedy that week. Rather, it was the last R&B chart Billboard would publish for more than a year. One week after this issue, the editors mysteriously pulled the chart from the magazine and kept it out for 14 months.

When Billboard brought back Hot Rhythm & Blues Singles in late January 1965, it looked markedly different: Its No. 1 song was the Temptations’ “My Girl”, and other than one Righteous Brothers song, the revamped chart included all people of color. Billboard’s editors never explained specifically how they changed the chart’s formula or the data gathered to compile it; the magazine carefully tends to its chart formulas, and over the years, all of Billboard’s major charts (there are dozens) have evolved along with changes in technology and American culture. But one thing was certain: The revamped 1965 R&B chart formula had been refined to focus more closely on record sales and radio listening by actual R&B fans.

And that’s the difference between the R&B chart led by Jimmy Gilmer in 1963, and the one led by Eminem in 2013: The former was based on a slipshod methodology, and Billboard fixed it. The latter is based on a new, also dubious methodology, powered by digital data, that over-weights pop crossover records. But this time, the magazine has no intention of changing it anytime soon.

Hot R&B/Hip-Hop songs is now essentially a condensed version of the Hot 100—and lovers of black music are deeply unsatisfied. What happened?

Getting the Formula (and the Limits) Right

Billboard has had a chart to track music aimed at African-Americans since the 1940s, but its size and methodology have changed multiple times over the years. To say nothing of its name—beginning with Harlem Hit Parade in 1942, the chart has been called everything from Race Records (1945–49) to Hot Soul Singles (1973–82). Since the 50s, some version of Jerry Wexler’s famous coinage “Rhythm & Blues” has appeared in the title more frequently than any other term; the chart’s current name is the comprehensive Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs. For decades, the chart was the largely unchallenged authority on the songs that, week to week, defined black America. But it took Billboard a while to get the formula right.

Like the Hot 100, which since its inception in 1958 has mixed together multiple pools of data to form one all-encompassing pop chart, Billboard unified its R&B coverage into a single tally in October 1958. This R&B chart combined sales of singles (then on 45 rpm vinyl), radio airplay and, for a brief time, jukebox plays. This mix of sales-plus-airplay makes for a vibrant and reliable Hot 100, and it should have done similarly for the R&B chart.

The problem back then wasn’t with the formula per se, it was with the data. Retailers and radio stations were reporting all manner of popular records with even a hint of a beat, by black or white artists, as R&B. In the 50s and early 60s, at a time when reliable data in the record business was hard to come by—and, not incidentally, the Civil Rights Act was still nonexistent—one imagines the magazine was having a tough time finding record-shop managers and radio programmers able (or willing) to accurately reflect what African-Americans were listening to and buying. The November 1963 chart led by “Sugar Shack” was the dubious result.

The specific reasons why Billboard put the R&B chart on hiatus that week in late 1963 are lost to history. But it’s not hard to guess—chart historians theorize that the increasing dominance of Caucasian pop hits was the culprit. When the R&B chart returned in early ’65, Billboard placed a cryptic note below the new chart, in which the editors alluded to the magnitude of the challenge in reinventing it:

“Kudos to all the disc jockeys, program directors and retail outlets for their splendid co-operation in helping to kick off the new r&b page. It is quite evident, and has been for some years, that the people engaged in all areas of r&b programming and retailing, are solid co-operative merchandisers. The rapport between r&b radio and retail outlets and the energies expended by both to build the r&b field is a page that could well be inserted into many other areas of the record business.”

This editors’ note is more than happy-talk to thank DJs and store managers. It reads as Billboard vouching for the black-oriented music business itself—reassuring the recording industry’s machers that it was legitimate to track what actual African-Americans listened to and bought.

The key difference between the revamped R&B chart and the Hot 100 was that Billboard refined the R&B chart’s formula to impose careful limits on what airplay and sales counted. It was clear that only radio stations specializing in R&B—and not Top 40 stations or other formats that might play rhythmic music—had their reported airplay baked into the chart. As for the retail component, the magazine now counted what it came to call “core R&B stores”: retailers, many black-owned, in cities that sold primarily R&B records to a largely, though not exclusively, black clientele.

The Heyday of the R&B Chart

The Heyday of the R&B Chart

This formula turned out to be Billboard’s special sauce; the revamped chart wasn’t going to track R&B music per se, but rather the R&B audience. Ultimately, what this approach meant was that the R&B chart was qualitatively different from the Hot 100 pop chart—both the songs on it and where they fell.

A closer look at that very first revamped R&B chart in January 1965 offers several examples. That week, the Temptations’ “My Girl” was on both the Hot 100 and the R&B chart, but it was already at No. 1 R&B and had not yet reached the Top 10 on the pop chart—the Motown classic was still in the process of crossing over and wouldn’t top the pop chart until March. Conversely, Shirley Ellis’s “The Name Game” was a bigger Hot 100 hit that week (No. 3) than on the R&B chart (No. 6, on its way to a No. 4 peak). And there were core R&B hits that would never be big pop hits—Alvin Cash & the Crawlers’ “Twine Time” was No. 8 on that January ’65 R&B chart, on its way to a No. 3 peak; but it would never get past No. 14 on the Hot 100. These differences are why an R&B chart with its own distinct pool of data matters.

By the 70s, the differences between pop-chart performance and R&B chart performance were even more stark. In 1971–72, the R&B chart sported occasional No. 1 hits that wouldn’t even make the pop Top 20, like Rufus Thomas’s “(Do the) Push and Pull” (No. 1 R&B, No. 25 pop) or Johnnie Taylor’s “Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone” (No. 1 R&B, No. 28 pop); or even the occasional smash that would miss the pop Top 40 entirely, such as Bobby Womack’s “Woman’s Gotta Have It” (No. 1 R&B, No. 60 pop). In July 1973, Billboard expanded the chart, then called Hot Soul Singles, from 60 positions to 100. Those additional 40 positions at the bottom would contain all manner of deep cuts that would never make the upper reaches of the chart—the Jackson 5’s “All I Do Is Think of You”, Syreeta Wright’s “Harmour Love”, the O’Jays’ “Family Reunion”, Al Green’s “Love and Happiness”—signaling the depth of black music in this era.

By the end of the 70s, acts like Parliament/Funkadelic, Teddy Pendergrass, and Tyrone Davis essentially had core R&B careers. A track or two by these acts would make the lower rungs of the pop Top 40, but the bulk of their Top 10 R&B hits wouldn’t even touch the Hot 100’s upper half, if at all. The bad news for such acts was that their lack of crossover generally meant lower label promotional budgets; the good news was that R&B success could sustain a career. And when pop crossover did happen, it really meant something. By the time the Commodores and Kool & the Gang started scoring Hot 100 No. 1’s at the turn of the 80s, they’d already racked up strings of R&B chart toppers since the mid-70s, presaging their pop success.

It also meant something when a white act charted R&B—the crossover validation worked the other way, too. Scores of acts that normally dominated the Hot 100 would occasionally record a song embraced by the R&B audience. Elton John has long attested to how thrilled he was when his “Bennie and the Jets” was the top song on black radio in Detroit and ultimately crossed to the R&B chart, where it peaked at a respectable No. 15. Other hits by white acts did even better, reaching the R&B chart’s Top Five: Average White Band’s “Pick Up the Pieces”, KC and the Sunshine Band’s “Get Down Tonight”, Wild Cherry’s “Play That Funky Music”, Bee Gees’ “You Should Be Dancing”, Rod Stewart’s “Da Ya Think I’m Sexy”, and, by the early 80s, Daryl Hall and John Oates’s “I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do)”. These songs didn’t chart high on Hot Soul Singles because someone in charge of the charts thought they sounded black enough—they crossed over because black radio stations and core R&B stores were playing and selling them in quantity.

(Payola surely played a role in those good-old-bad-old days, as it did throughout the 70s and 80s on the pop charts and rock radio. But R&B chart success in and of itself likely wasn’t a lucrative enough prize for labels to budget serious “incentives.” Anyway, as the evidence shows, the aforementioned white acts only occasionally scored serious R&B hits. If Warner had wanted Rod Stewart to have more than one R&B smash—rather than the solitary one he did—they’d have greased more palms.)

By the 80s, the R&B chart was its own demimonde with its own lineup of stars. On the surface, the chart had a more racially defined identity: In 1982 Billboard, not without controversy, renamed the chart Hot Black Singles, even though white acts like Hall & Oates, Madonna, Phil Collins, George Michael, and Lisa Stansfield sporadically charted R&B.

But these occasional appearances by white acts didn’t affect the chart in any major way during the decade of Michael, Lionel, Prince and Whitney—black music was doing just fine, thank you, both on the Hot Black Singles chart and on the Hot 100. In addition to the major inroads made at Top 40 radio by these megastars, a lower tier of core black superstars gave the 80s R&B chart its own distinct identity: Luther Vandross, the Gap Band, Freddie Jackson, Maze, Stephanie Mills, Melba Moore, Guy—with rare exception, these artists’ strings of top-charting R&B hits would bypass the pop Top 40 entirely. Indeed, what made the 80s one of the richest decades for black pop in a generation could be seen each week right at the top of Hot Black Singles—one week, Michael Jackson’s über-crossover hit “Billie Jean” could be on top, and then a week later, it would be replaced by a record as un–Top 40–friendly as George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog”.

Even in this rich period, the chart wasn’t perfect: Hip-hop, in its early days, was badly underrepresented on Hot Black Singles. But mostly, that wasn’t the chart’s fault. As has been well documented—particularly by the founders of the Def Jam label—black radio, then dominated by the smoothest forms of buppie-R&B, was slow to accept hip-hop, even as early rap singles were selling thousands or even millions (a phenomenon that also went underreported by record retailers).

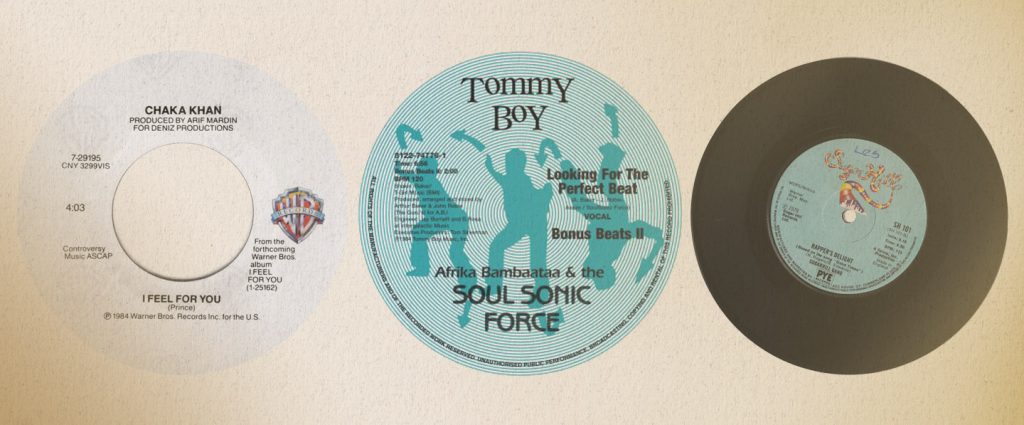

At the start of the decade, a foursome of vital rap tracks all peaked, coincidentally, at No. 4 R&B: the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” and Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks,” both in 1980; and Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force’s “Planet Rock” and Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s “The Message”, both in 1982. But No. 1 rap songs were scarce. To be sure, rap elements graced numerous 80s chart-toppers, including Cameo’s “She’s Strange” and Chaka Khan’s “I Feel for You”, but by the end of the decade, only two full-on rap songs, total, had topped Hot Black Singles: L.L. Cool J’s crossover ballad “I Need Love” in 1987, and De La Soul’s psychedelic P-Funk reinvention “Me, Myself & I” in 1989. (Run-DMC did just OK, never getting past No. 5 R&B with “My Adidas”.)

By the end of the decade, a follower of the black chart could be forgiven for thinking rap was basically a fad. But as it turned out, the 80s were a mere throat-clearing for hip-hop’s 90s explosion. And good data had a lot to do with giving rap its due.

SoundScan Ushers in an R&B/Hip-Hop Chart Boom

The deep-data era on the U.S. charts began in May 1991, with the introduction of SoundScan (later Nielsen SoundScan) technology—accurate tallying of sales at the retail counter, through scanned UPC barcodes on music purchases to Billboard’s flagship album chart. Immediately, this revolutionized the chart, giving a boost to genres that the old manual-charts system had underreported. In particular, hip-hop and country artists benefited massively when sales were tallied more accurately.

Then in November 1991, the magazine brought SoundScan technology to the Hot 100. Because the Hot 100 was based not only on sales of singles but also radio airplay, Billboard introduced a computerized data feed from Broadcast Data Systems, which counted radio plays via a sonic fingerprint. While BDS didn’t eliminate recording industry payola, it made it much harder for labels to pay for a “paper” (phony) playlist add; the Hot 100 was now based on songs receiving actual airplay. Once again, the changes to the Hot 100, thanks to both BDS and SoundScan, were profound—it’s difficult to imagine Sir Mix-a-Lot topping the Hot 100 for over a month in the summer of 1992 without the more accurate technologies.

In 1992, the SoundScan and BDS technologies made their way to the black-music chart (two years earlier, the chart had been renamed again, this time as Hot R&B Singles). Billboard was so careful about not screwing up their R&B retail/radio formula—many small retailers couldn’t afford barcode scanners at first—that the magazine phased in the new technologies over several months to be sure they didn’t misrepresent what black retailers and stations were playing. But once the new formula was in full effect, by the start of 1993, rap’s profile on Hot R&B Singles improved almost immediately. Within the first three months, Naughty by Nature and Dr. Dre scored their first No. 1 hits on the more data-accurate R&B chart.

For the rest of the 90s, rap became so omnipresent on Hot R&B Singles—with 2Pac, Notorious B.I.G., Puff Daddy, Ma$e, and Missy Elliott scoring hits—that in 1999 Billboard finally added hip-hop to the name of the chart, redubbing it Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles & Tracks (a mouthful of a name that was mercifully shortened to Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs in 2005).

Of course, hip-hop wasn’t only dominating the R&B chart in the 90s—it was steadily taking over the Top 40, too. As early as 1993, black music was already so dominant on the Hot 100 that all but two of Billboard’s top 25 pop singles of the year were crossover tracks from the Hot R&B Songs chart (the only exceptions that year: one track each by UB40 and Soul Asylum). There were periods in the late 1990s and early 2000s where the Top 10 of the Hot 100 and R&B chart looked very similar. But that was largely because so many R&B and hip-hop tracks were legitimately crossing over to the pop charts—phenomena that SoundScan and BDS tracked accurately.

The death of the retail single by the end of the 90s helped accelerate the R&B-to-pop crossover. Wanting to motivate full-length CD purchases whenever possible, the major labels began pulling major radio hits from the retail market; if you wanted a Green Day, No Doubt, or Goo Goo Dolls hit, you had to pony up $16–$18 for the CD. While hits by both white and black acts were pulled from the retail market, songs by rock and pop were generally less available—a kind of racial profiling that implied that white consumers were more likely to buy a full-length CD. If you were a Britney Spears fan from 1999 to 2003, you’d buy her CD; many of Spears’s biggest radio hits, including “Oops…I Did It Again” and “Toxic”, weren’t released as singles. If you were, say, an OutKast fan, you might buy Stankonia, but you might just as easily purchase “Ms. Jackson” as a CD-single. The result was that, at the turn of the millennium, the Hot 100 was more dominated by hip-hop and R&B than teen-pop, which tended to do better on the album chart.

Still, even with these singles-yanking shenanigans going on, it was undeniable in the early 2000s that music by African-Americans had come to be preferred by a generation of teenagers and twentysomethings, and black radio at the peak of hip-hop was scoring ratings and influencing Top 40 like never before.

By 2004, literally every song that topped the Hot 100 was by a person of color. This was the final affirmation that black music—during the peak of Usher, Destiny’s Child, 50 Cent, and Jay-Z—was, to borrow Berry Gordy’s term, the sound of young America. In some cities, even the Top 40 pop stations leaned strongly “rhythmic,” in industry parlance. The R&B chart didn’t look terribly different from the Hot 100 in 2004, but that was largely because Top 40 radio was using the R&B chart as its first stop to go shopping for hits. R&B and hip-hop were setting the agenda.

Within a year, however, that pendulum would begin swinging back.

Black Music’s Digital Problem

The iTunes Music Store opened for business in 2003, revolutionizing the legal distribution of music online. Billboard waited a couple of years to incorporate digital song data into its charts, giving Apple’s online platform and iPod ecosystem time to disseminate past early adopters to teenagers and a wide range of demographics. Finally, in February 2005, digital sales—dominated, overwhelmingly, by iTunes—were baked into the Hot 100, and the digital era on the charts began.

The effects were remarkable, even within the first year. Million-selling songs like Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl” and Weezer’s “Beverly Hills” gave the 90s veterans their highest-charting Hot 100 hits ever. Within just a few years, thanks largely to digital sales, soft-rock acts like Plain White T’s, Coldplay, and Owl City were topping the charts; and budding country stars Carrie Underwood and Taylor Swift were breaching the pop Top 10, thanks in part to the democratizing effects of digital sales, which balanced out slow-moving radio rotations on the Hot 100.

Over on Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs, however, those millions in digital sales had no impact. Billboard still wasn’t factoring iTunes and its ilk into its black music chart in the late 00s; only physical singles sales still counted. To say the least, this was a rather surreal chart policy for the time. If the new millennium had been tough on brick-and-mortar music chains—shuttering the nation’s Tower Records, Coconuts, and Strawberries franchises—it was downright brutal on the smaller shops that reported to Billboard’s R&B charts, which were disappearing just as quickly. And anyway, so few physical singles were being released in the 00s that whatever black-owned-and-oriented music stores remained didn’t have much to report to the chart.

For all intents and purposes, then, during the 00s, Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs was an all-radio chart. Physical singles sales still counted but had an infinitesimal impact. This overreliance on radio made the chart rather hollow; as vital as black radio is as a medium, it is subject to the same over-research, promotional manipulation, and slow playlist turnover as Top 40 radio. By 2009 and 2010, fewer than 10 songs were topping the R&B chart all year.

Add to the mix a slump in black radio in the late 00s, brought on by radio’s new ratings technology, the Portable People Meter, which replaced the prior handwritten diary system. PPM, a more accurate (though far from perfect) pager-like listener-measuring device, became Arbitron’s main method for gathering radio ratings after 2007. It revealed that urban radio wasn’t scoring the persistent listenership previously believed—in no small part because Top 40, adult-contemporary, and rock stations were more likely to be playing in public spaces—which led to decimated ratings and the shuttering of stations; in New York City, two powerhouse black stations, Kiss-FM and WBLS, were compelled to merge.

Billboard couldn’t do anything about the slump in black radio ratings. But clearly, for the R&B/Hip-Hop chart to remain vital, digital consumption of black music would have to be baked in somehow. However, for nearly eight years—even as the Hot 100 became reenergized by iTunes, and eventually Spotify (added to the Hot 100 in 2012), and YouTube (2013)—Billboard’s editors resisted adding digital consumption data of any kind to the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart.

They likely had their reasons. Because here’s the problem with digital and R&B: There’s no such thing as a “black iTunes” or a “black YouTube.” African-Americans—and hardcore hip-hop and R&B fans of any ethnicity—mostly go to the same sites to purchase and stream songs as everyone else. You can imagine a world where, say, BET or The Source had started a download store or streaming site; then all Billboard would have to do to modernize its R&B chart would be to draw all digital sales data for the chart from those outlets. (Sites like WorldStarHiphop let you stream both mainstream and underground videos, but they don’t sell enough stuff to be helpful to Billboard.) In the winner-take-all game of digital music consumption, any such site would get crushed by Apple’s iTunes and Google’s YouTube.

This all-encompassing digital consumption isn’t necessarily a problem when it comes to the Hot 100, which covers all genres and where, in theory, all songs compete on equal footing. But since its reinvention in 1965, the whole point of Billboard’s R&B chart has been to highlight sales and airplay targeted at core black music fans. That’s what distinguished the R&B chart from the Hot 100. How do you do that, if you can’t isolate sales and streams generated by these consumers?

A Solution Causes Even More Problems

As late as the summer of 2012, digital sales still weren’t incorporated into the R&B/Hip-Hop chart. That’s when I wrote an installment of my former Village Voice column “100 & Single” highlighting the growing “commercial funk” in black-oriented music and calling on Billboard to add digital data to the chart. “Music charts are like feedback loops,” I wrote. “They reflect popularity back at the industry that makes stuff popular. But the loop on this chart is getting smaller and more insular all the time.”

Granted, I have about as much influence on Billboard chart policy as you do—i.e., none. But as long as I was thinking out loud about how the magazine could modernize the chart, I also warned that, whatever they did, they shouldn’t just throw in all digital sales of any song that could qualify under the broadest definitions of hip-hop and R&B because, as I wrote, “a digital-fueled R&B/Hip-Hop chart would probably vastly overstate the urban popularity of will.i.am.” Then, three months after that column, Billboard did exactly what I was afraid of.

In October 2012, the magazine announced an overhaul to its R&B/Hip-Hop, Country, and Latin Songs charts, all incorporating digital sales and streaming for the first time. The modernization of these genre charts was long overdue, but Billboard threw out the baby with the bathwater. Or, you might say, drowned the baby in too much bathwater: Now, digital sales from any source, any buyer (read: pop fans) would be factored into each chart. Worse, in order to achieve sales and radio parity, Billboard also incorporated airplay across all radio formats into the genre charts; so airplay from Top 40 or adult-contemporary stations of, say, an R&B song would now count for the R&B chart, of a country song would count for the country chart, and so forth. In essence, Billboard would now use the exact same data set for these genre charts that it uses for the Hot 100, and simply trim the charts back to whatever songs the magazine determined fit that genre—each chart became a mini–Hot 100.

The word that recurred throughout Billboard’s announcement of the chart changes was “crossover”: “The new methodology, which will utilize the Hot 100’s formula of incorporating airplay from more than 1,200 stations of all genres monitored by BDS, will reward crossover titles receiving airplay on a multitude of formats.” This was an acknowledgment that the mass of pop fans was going to control the fate of the genre charts. It was also ironic, since these changes would largely make “crossover” as we previously knew it—songs transitioning over a matter of weeks or months, from genre chart to mass audience—impossible.

Followers of these genre charts were instantly unhappy. Fans of Hot Country Songs were aghast at the changes; the very first week of the switch, an especially poppy Taylor Swift song that wasn’t scoring much airplay on country radio stations shot to No. 1 on the revamped Country chart. On Latin Songs, the steady turnover of hits atop the chart slowed down instantly, as a crossover hit that paired reggaetón stars Wisin y Yandel with Chris Brown and T-Pain vaulted to No. 1 and settled in for a months-long run. Even Billboard’s smaller charts weren’t immune. Hot Rap Songs, a sidebar to the R&B/Hip-Hop chart that had existed since 1989, also had digital data added to its formula; but rap fans howled when the first No. 1 song on the revamped Hot Rap Songs was K-Pop star Psy’s viral hit “Gangnam Style.”

Arguably, though, the biggest loser in the 2012 charts overhaul was Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs. Billboard cut the chart in half, from 100 to 50 positions—its smallest size since the early 70s. Unlike the country and Latin charts, which hadn’t had a sales component, the R&B chart had once been fueled by singles sales at core R&B stores. Replacing that with undifferentiated iTunes sales was like replacing Sylvia’s with McDonald’s. Finally, while all of the genre charts were now stuffed with multi-format radio airplay, the effects were more noticeable on the R&B chart, which became exceedingly skewed toward pop-radio-friendly songs.

Top 40 stations rarely play Latin music, and they play only a small selection of country titles; but they play a lot of music that falls under the broad umbrellas of “R&B” and “hip-hop.” I place these terms in scare quotes because, while Justin Timberlake certainly qualifies as R&B-pop and Macklemore does rap, there was a reason neither of these acts topped Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs under its old methodology—they weren’t core artists for the genre. After the overhaul, Macklemore topped the R&B/Hip-Hop chart for five months straight, and Timberlake monopolized multiple spots within the chart’s Top 10 throughout 2013. With these crossover artists selling millions online and racking up hours of cross-genre airplay, dominance on the revamped R&B chart was inevitable.

Clearly, race is the elephant in the room in these discussions of who is worthy of the R&B/Hip-Hop chart. But it’s not as simple as “black: good; white: bad”—again, the R&B chart has historically included, and even been topped by, certain songs by white acts. The problem goes beyond race; the new methodology has skewed results for artists on either side of the color line.

Take Rihanna: native of Barbados, obviously a woman of color and, let’s be clear, primarily a pop star. Since her 2005 breakthrough, she has been tentatively embraced by R&B radio, but only intermittently. Until 2012, she’d only scored one No. 1 R&B hit, the 2008 ballad “Take a Bow”; that’s compared with her 10 chart-toppers on the Hot 100 in this period. Many of Rihanna’s Hot 100 No. 1s—songs as massive as “Umbrella” and “Disturbia”—were R&B chart underperformers (Nos. 4 and 88 R&B, respectively). But under Billboard’s new R&B/Hip-Hop chart formula, all of the megastar’s millions in sales and radio audience count, regardless of their source. The week in 2012 that Billboard kicked off the new R&B chart, her “Diamonds”, a song receiving only modest black radio airplay, shot from No. 66 to No. 1 under the new methodology.

On the other side of the racial divide, consider Robin Thicke. He may be a punchline at this point, but during the mid-00s he was, no joke, a legitimate urban radio star—the leading blue-eyed soul singer of his day. His 2007 slow jam “Lost Without U”, an 11-week R&B chart-topper under the old, black-radio-driven system (Hot 100 peak: No. 14), was the No. 1 R&B song of ’07 (and the first track by a white artist to rank as the year’s top R&B song since the chart changed in 1965).

The new 2012 methodology didn’t hurt Thicke—it boosted him in the wrong way, killing whatever cred he had. “Blurred Lines”, Thicke’s 2013 bid for pop crossover, succeeded like gangbusters on the Hot 100—it was his first Top 10 pop hit and eventually topped the big chart for 12 weeks. As for R&B/Hip-Hop, under the old chart system, you could imagine “Blurred” hitting the top for a week or two, if for no other reason than Thicke’s strong track record with the R&B audience. Instead, under Billboard’s new everything-and-the-kitchen-sink formula, “Blurred” topped the R&B/Hip-Hop chart for an absurd 16 weeks, making Thicke look less like the integral part of black radio he once was and more like a white interloper.

The reason songs like “Blurred”, or Rihanna’s “Diamonds”, or Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’s “Thrift Shop”, can command the new R&B/Hip-Hop chart for so long is that Billboard’s overhauled genre lists are essentially what I call “accordion charts”: condensed versions of the Hot 100, with all the songs that Billboard has decided don’t qualify for that genre taken out. You could actually make any week’s R&B/Hip-Hop chart yourself: Take that week’s Hot 100; cross out the pure-pop, country, and rock songs; and re-stack all the songs that are left, keeping them in the same order. Voilà: instant R&B chart.

(To satisfy my curiosity for this story, I played the create-the-R&B-chart game with four different Hot 100s from various weeks throughout 2013. The only differences between my handmade R&B charts and Billboard’s official ones were the inclusion of older songs on lower rungs of the R&B chart that Billboard removes from the Hot 100 due to its recurrent rules that prune old songs. If these records had been left on the Hot 100, my faux R&B charts and Billboard’s would have been identical.)

An analogy: Imagine if we changed the way we elected U.S. senators. Under our new rules, we’d take each state’s presidential vote and just redistribute the Democratic and Republican votes among the two corresponding Senate candidates—ignoring the fact that candidate specifics, party-switching, and voter turnout have something to do with how we vote. A system like this would certainly make the process of electing senators simpler, and the result might vaguely resemble the outcome of our actual system. But it would change the outcome in close races; it would remove voter agency (a Democratic Senate hopeful would have no incentive to campaign for moderate Republican voters, or vice-versa); and it would dumb down the (already pretty dumb) process.

Billboard’s new accordion-style genre-chart methodology, with the Hot 100 playing the part of the presidential vote, is not much better than that. All the interesting quirks that make one song a better fit for the core R&B audience and another a pop crossover smash are eliminated. This approach isn’t the way Billboard’s genre charts are supposed to work; they are supposed to be based on a different sample of data—not just the Hot 100 data, editorially pruned by Billboard.

Emphasis on editorial: What is perhaps worst about this system is how Billboard, supposedly objective chart-maker, is now in the sorry business of trying to decide who qualifies for an R&B chart, with all the bizarre identity implications. Justin Timberlake and Eminem? In. The biracial Bruno Mars, or the Mariah Carey–like Ariana Grande? Out. I don’t have any better grasp on whether these artists should qualify for the chart than Billboard does. But the magazine is playing a role that used to be played organically—by shoppers at black retail stores and R&B radio—on a song-by-song, artist-by-artist basis.

But Can the Chart Be Fixed?

For all my disdain for the current thinking behind the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, I have sympathy for Billboard’s editors—they’re currently in a no-win situation when it comes to the digital era and audience measurement. If I were in charge, I’m not sure I could do any better. Admittedly, any sort of “fix” would be a touchy and labor-intensive task.

Late last year, while researching this piece, I reached out for commentary from Silvio Pietroluongo, who’s been with Billboard more than 20 years and is now their Director of Charts. (Disclosure: A very long time ago, I wrote a handful of articles for Billboard as a freelancer; but never as a chart analyst, and no more recently than 2003. The editor I wrote for—not Pietroluongo—is no longer with the magazine.)

First off, chart grumblers should get comfortable with the current state of affairs. “We are always exploring ways to improve our charts,” Pietroluongo wrote, “but at the moment we have no plans to change Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs, except for increasing our pool of streaming services, as would be the case for any of our other sales/airplay/streaming charts.”

I also asked about the addition of all-genre radio data to single-genre charts like R&B/Hip-Hop. I can understand Billboard not being able to pull apart digital sales by audience, but why compound the error by throwing in pop airplay? Pietroluongo says it wasn’t about black radio’s lower, PPM-damaged ratings, but about apples-to-apples parity—if Billboard is going to count all buyers, it has to count all radio listeners.

“[This move] had nothing to do with urban radio’s plight,” Pietroluongo wrote. “[It’s] just as a way to measure full radio consumption, in the same way we measure the entire digital download market and across-the-board streaming activity. This was a more logical formula than using partial radio airplay with complete sales and streaming.”

When asked whether the revamped chart serves the music industry as an accurate reflection of the state of black or “urban” music, Pietroluongo wrote: “I believe it gives an accurate reflection of the popularity of R&B/hip-hop music [emphasis his] across multiple music metrics, which was our goal. The chart, as previously constituted, was 98% based on airplay from R&B/hip-hop radio stations, and that ranking (now R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay) continues to exist as a barometer of songs that are popular at that radio format.”

Indeed, fans of the pre-2012 system can check out the R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay chart, which is virtually identical to the old methodology. As Pietroluongo implies, when the physical singles market died in the 2000s, the big R&B/Hip-Hop chart was essentially all-airplay, anyway.

But as its name indicates, the R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay chart only covers radio; and the whole reason the main R&B/Hip-Hop chart needed refreshed sales data in 2012 was it had gotten radio-heavy, small-ball, and dull. The strength of the old R&B/Hip-Hop Songs—before the 2000s, anyway—was its mix of radio and consumer data.

Which brings us to the no-win situation: We fans—and, presumably, the music industry—asked Billboard to add digital data to the R&B/Hip-Hop chart, and Pietroluongo’s team complied. Now we’re complaining about them adding, in essence, too much digital data.

Remember that what made the pre-2000s R&B/Hip-Hop chart work was that it sought to measure the boundaries of an audience, not a genre. If listeners and buyers of black music collectively decided they liked a song—even it were by Bee Gees, Hall & Oates or, to pick a modern example, Lorde—it would appear on the chart, and its chart performance would depend on their purchases and listenership, not on everybody’s. The question is: How do you pinpoint this audience in 2014?

Apple, to take the most prominent example, doesn’t provide demographic breakdowns of its buyers—nor, arguably, should it. Neither does Google, parent of YouTube—it’s none of these companies’ business (well… insert NSA joke here). And anyway, if the U.S. census can’t come up with a straightforward way to measure who is a person of color, it’s silly to expect a technology conglomerate to do so.

Let me reiterate: The solution is not a set of data that racially profiles users. It’s tempting to cut sales and streaming data by ZIP code; both George Clinton and Chris Rock have quipped that African-Americans mostly live in about “10 places” across the country. But that would be too limiting, and anyway, we don’t want Billboard asking Apple, Google, Amazon, Spotify et al., “Tell us what songs your black users are buying and streaming,” even if such a thing were possible. What we want is a recreation of Billboard’s old “core R&B stores” model: limiting the pool, as best as can be approximated, to a music-buying clientele that purchases mostly R&B and hip-hop music—then asking them what they’re buying now. Is that even possible? Again, if there are no distinctive online gathering places for R&B and hip-hop fans to buy or stream music, sooner or later you’re going to have to place individual users in buckets, even if those buckets aren’t race-based.

You can understand why Billboard would find such data-gathering headache-inducing and ill-advised. Pietroluongo told me Billboard ruled it out: “We felt it was best to move to a ranking that measured the popularity of the genre of R&B/hip-hop music, and one that was not based on demographic or regional purchases, even if that option existed. Does the consumption of country music in New York or Los Angeles mean something different than that purchased in Kansas or Nebraska?”

I half-agree that regional patterns might not be advisable; and demographics are fraught. But imposing no limitations whatsoever on the audience parameters has resulted in the dubious, mini–Hot 100 version of the R&B/Hip-Hop chart we have now.

Streaming to the Rescue

The digital era is what got us into this mess—the fallacy of the “long tail” turning into the big-get-bigger economy, as everybody piles into the same few websites to consume their music. But if digital created the R&B/Hip-Hop chart dilemma, can’t digital can also solve it? The answer may not come from Apple’s iTunes, or Google’s YouTube, but rather the youngest and smallest (but fastest-growing) music consumption format: streaming.

Sometime this winter in your social media feed, you may have seen a blue U.S. map, with each state labeled with the name of a quirky musical artist. The map called these “regional listening preferences,” but your friends might have posted it on Facebook as “every state’s favorite artist!” This turned out to be one of 2014’s most misunderstood music memes—the map wasn’t meant to show each state’s ”favorite” artist; it was meant to show how each state was distinct from one another. Using piles of streaming data, the map identifies the act that was most unique to that state. For example, for Tennessee, the map offers Juicy J; he’s not the most popular act in Tennessee, but rather the artist most likely to be streamed in Tennessee compared with any other state. In short, the map is a breakdown of granular regional preferences and a showcase for how music-consumption data can be sifted very finely.

It was created by Paul Lamere, a technologist at the Echo Nest, a music intelligence company whose algorithm, developed at M.I.T., powers the music-recommendation engines of MTV, eMusic, and Vevo, among many platforms. Just last month, the Echo Nest announced it had been purchased by Spotify, one of its biggest clients—giving the company even greater market clout with one of the fastest-growing services supplying data to Billboard’s charts. The main point of Echo Nest’s technology is to determine as much as possible about an individual listener, in order to recommend additional, very specific music that that listener might also enjoy. But as the map experiment reinforced, even with data as simple as a ZIP code, streaming services can aggregate large amounts of data to track subsets of users and detect patterns by region.

Or, perhaps, patterns by genre—in a recent interview with John Schaefer about the blue map on the WNYC radio program “Soundcheck”, the Echo Nest’s Lamere said the platform’s data was only getting more refined: “As soon as you start to know a little bit about the people’s specific tastes—where they’re from, how old they are, and also what kind of music they actually like to listen to [emphasis mine]—we can do a lot better job of understanding them and giving them a good listening experience.”

Imagine if the Echo Nest harnessed its platform—without identifying individual users by name, demographic, or location—to pinpoint a subset of listeners who primarily listen to contemporary R&B or hip-hop. (Or country. Or Latin music.) It would be fairly straightforward to aggregate just those listeners, and then chart their favorite songs weekly. This imagined system, based on a bucket of R&B/hip-hop super-listeners, would capture all of the new hip-hop and R&B they were consuming. And if a mass of these listeners collectively decided they liked an occasional, poppier song by Lorde or Adele, it would capture that, too.

The Echo Nest could, in essence, become the next SoundScan, rebuilding the core R&B record store of yore in digital form—no racial profiling required. Billboard would have its audience-specific data back and could pair it with data from black radio to reconstitute the R&B/Hip-Hop chart in modernized form.

A pipe dream? Perhaps, especially as long as iTunes—with its undifferentiated, mass-market sales data—remains the world’s largest music retailer. But Apple may not be atop the music-consumption pyramid much longer: U.S. digital music sales peaked roughly a year ago and have begun a steady decline as more users switch from buying to streaming (and the computer giant’s new iTunes Radio platform has proved less profitable than expected). It also might be a while before Billboard could attempt a reconstitution of the R&B/Hip-Hop chart’s special sauce while technology and consumer habits catch up. The digital divide may still be limiting the number of African-American users of services like Spotify—although huge smartphone penetration rates among blacks are quickly closing that gap.

Of course, all this speculation assumes the magazine’s editors even care to remake the chart once again. Billboard’s apparent strategy, now that the initial carping about the genre charts has died down, is to just wait out a cultural pendulum swing back toward black-oriented music.

And four months into 2014, the R&B/Hip-Hop chart is looking a bit less pop-skewed. A big reason why the chart looked so exceedingly white in 2013 was that the Hot 100 was itself extra-white last year—not a single lead black artist topped the pop chart all year. But Pharrell Williams broke the drought last month, topping the Hot 100 with “Happy”. Of course, because he’s No. 1 on that chart, he’s also No. 1 on Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs. But what hasn’t changed is the R&B/Hip-Hop chart’s second-class, kid-brother status, as a cropped clone of the Hot 100. Top 40 radio and millions of iTunes buyers now define what Billboard calls an R&B hit—pop fans love them some “Happy”—and actual crossover as we used to know it is a thing of the past.

Given what they had to work with, Billboard did what it had to do to bring the R&B/Hip-Hop chart into the 21st century. But the technology will soon exist, if it doesn’t already, to do it for real and track the popularity of songs among an authentic, believable, legitimate coterie of black music fans. Restoring R&B/Hip-Hop Songs as an audience chart, not a genre chart, would uphold a great, multi-decade tradition. It would do right by an audience that has been consistently ahead of the curve in popular music.

This is the audience that gave James Brown and Aretha Franklin their first major hits, long before they graced the pop Top 10; that gave Lionel Richie his first No. 1 hit a decade before he went solo; that defined the terms “quiet storm” and “slow jam” before they became late-night TV punchlines; that gave a young Prince a home for his sound before the world knew he could rock; that broke Whitney Houston when she was still an ingénue; that stuck by Michael Jackson when Top 40 radio abandoned him; and that established Lil Wayne as the new millennium’s hip-hop polymath. African-American music is a continuum, not just an ingredient in the pop stew. It deserves its own barometer for success.

Followup coverage: A few weeks after the publication of this Pitchfork article, I was interviewed by The New Yorker‘s Sasha Frere-Jones about the issues raised in “I Know You Got Soul.” https://www.newyorker.com/culture/sasha-frere-jones/fixing-the-charts