Signed, Sealed, Delivered, I’m Yours

Stevie Wonder’s hit songs written for others are so wide-ranging, you might not see his fingertips.

At Motown’s 1966 Christmas party, the story goes, Smokey Robinson was handed a near-complete instrumental track and invited to finish it. Robinson, perhaps Motown’s greatest songwriter, typically worked alone. He was the sole writer-producer of such chart-toppers as 1964’s “My Guy” for Mary Wells and 1965’s “My Girl” for the Temptations. But Robinson had yet to achieve his own No. 1 pop hit as a performer. That is, until he got his hands on that track, which would become “The Tears of a Clown”—Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ first chart-topping song on Billboard’s Hot 100 and one of the most celebrated recordings in Motown history. While Smokey did write “Clown’s” ingenious lyrics, its durable instrumental track—built around a calliope-like melodic hook and a sax-drenched bassline—was the handiwork of Motown producer Hank Cosby and 16-year-old Stevland Hardaway Morris.

Yes, the teenager known just three years earlier as “Little” Stevie Wonder gave Smokey Robinson his only No. 1 pop hit.

Stevie Wonder is such a force of nature, it’s hard to think of him being in the background of anything. That includes giving songs away—some of the best stories about his career are of songs he toyed with passing to others but wound up keeping for himself. Frequent collaborator Lee Garrett says their co-penned 1970 hit “Signed, Sealed, Delivered, I’m Yours” (No. 3 on the Hot 100) was conceived for Stax singer Johnnie Taylor, before Wonder realized the song was too good and recorded his own version. Even more famously, “Superstition,” Wonder’s greatest single recording, was inspired by and penned expressly for electric-guitar maestro Jeff Beck as a thank-you for playing on Wonder’s 1972 album Talking Book. But Motown chief Berry Gordy wisely insisted Wonder retain it for his own disc, and it shot to No. 1 on Billboard’s pop and soul charts in January 1973. (Beck released his hard-rocking version of the song the following spring.)

Despite these tales, Wonder did indeed pen many songs for others, some of them huge hits. He is even a bit underrated in this regard, partially because of Wonder’s reputation as a self-contained auteur and multi-instrumentalist on his own classic albums, and partially due to his own staggering catalog of hits (10 No. 1s on the Hot 100, and 18 more Top 10s; a stunning 19 No. 1s on the R&B chart). But the main reason we don’t think of Stevie Wonder as a trendsetting force beyond his own records—unlike, say, Prince—is that the hits he produced for others were more intermittent, and their sonic palette so wide-ranging. They retain signature elements of his sound but are remarkably broad in style and melodic approach.

Take the Spinners’ hit “It’s a Shame” (No. 14 pop, No. 3 R&B). Like “Signed, Sealed, Delivered,” it’s a 1970 composition by Wonder, Garrett, and Syreeta Wright, Stevie’s soon-to-be-wife (and an artist in her own right). In fact, Garrett notes, Wonder presented the basic melodies for both songs to him and Wright virtually back-to-back. The result: “Signed” and “Shame” are mirror images of each other, with similar bones but emphasizing different Stevie-like elements. “Signed,” the song Wonder retained, relies on another of his sturdy brass-and-bass lines (like “Tears of a Clown”), but it opens with a descending eight-note filigree, played on a sitar, that lurks occasionally in the background. Whereas “Shame,” the one he gave away to the Spinners, is totally dominated by its own eight-note filigree—a syncopated hook, this time on guitar—that behaves like a relentless earworm (or even a sample, before the age of sampling). The two singles are twins—but fraternal, not identical.

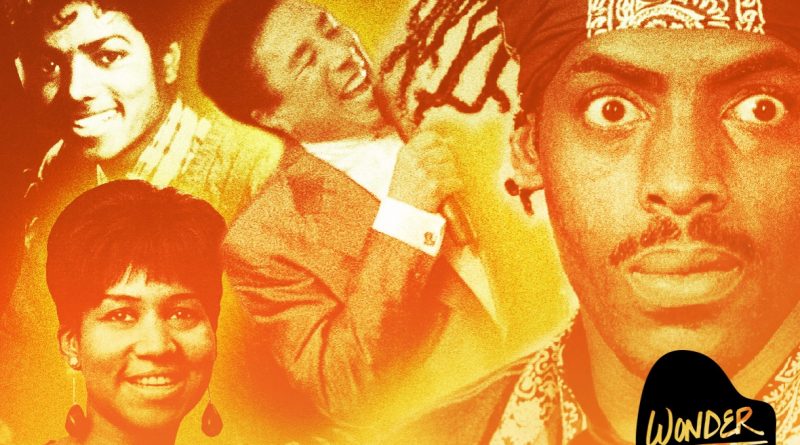

This pattern recurred for the next decade. The hits Wonder wrote or produced for others at his ’70s peak reflected whatever styles he was exploring at the time, but emphasized different components of his sound. Aretha Franklin’s “Until You Come Back to Me (That’s What I’m Gonna Do)” was a song Stevie co-wrote and recorded in 1967 but left unreleased. Accordingly, Franklin’s version, a chart-topper in early 1974 (No. 3 pop, No. 1 R&B), felt like a revival of Wonder’s late ’60s sweet–soul music. Whereas later in ’74, the Chaka Khan–led band Rufus had its chart breakthrough with the Stevie-penned “Tell Me Something Good” (No. 3 pop and R&B), which couldn’t be more different from the Aretha hit—“Good” is a slice of lurching funk that fully reflected Wonder’s Innervisions sound. The next year, Wonder produced and played keyboards on Minnie Riperton’s timeless 1975 chart-topper “Lovin’ You” (No. 1 pop and R&B)—a reflection of his gentlest ’70s synth ballads.

Perhaps the purest Stevie Wonder bake-off is the pair of tracks he wrote back-to-back in 1979 and 1980 for two different Jackson brothers, Michael and Jermaine. The songs reflect totally different sides of Stevie: “I Can’t Help It,” an album cut on Michael Jackson’s 1979 blockbuster Off the Wall and a black-radio standard that’s been much-covered by jazz artists, is a breezy midtempo ballad, anchored by Fender Rhodes and deep bass, that Stevie wrote expressly for Michael’s fluttery voice. It’s of a piece with the ethereal sound Wonder was exploring that same year on his Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants. Just months later, Wonder produced and wrote a slamming chart-topping single for Jermaine Jackson, “Let’s Get Serious” (No. 9 pop, No. 1 R&B). Wonder’s own vocals are audible on the track, which Jermaine sings in such a Stevie-like cadence that “Serious” could easily have wound up on Wonder’s own synth-funk 1980 opus, Hotter Than July.

Pop, Race, and the 60s: A Slate Academy

Join Slate pop critic Jack Hamilton for a bold re-examination of the music of the ’60s, and the tangled relationship between pop and soul, music and politics, entertainment and struggle.

For the rest of the 1980s, Wonder continued writing for other major acts—penning album cuts for everyone from Paul McCartney to Dionne Warwick to Eddie Murphy—but he kept the big hits for himself as he steadily grew less prolific. During this period, Wonder made the greatest impression on others’ records as an instrumentalist, contributing signature harmonica solos on smashes by Elton John, Chaka Khan, and the Eurythmics. However, the Stevie Wonder songwriting credit made a comeback in the ’90s, thanks not to a new burst of creativity on Wonder’s part but to the growth of cleared samples in hip-hop. Because Wonder retained tight control over his copyright, he exerted influence over the finished products.

The No. 1 song of 1995, Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise,” was built entirely around Wonder’s 1976 Songs in the Key of Life cut “Pastime Paradise.” When asked by Team Coolio for his blessing for the update, Wonder rejected an early version that included cursing. So Coolio recut the track to remove the profanity (likely making the song a bigger smash in the process—thanks, Stevie). Four years later, actor-rapper Will Smith dove right back into Songs in the Key of Life—and because the Fresh Prince likes to sample huge, recognizable hits, he picked an even bigger track from Stevie’s album, the 1976 No. 1 hit “I Wish.” Smith grafted Stevie’s classic onto the hook from a 1988 Kool Moe Dee single to form “Wild, Wild West,” a No. 1 single from Smith’s 1999 movie of the same name. According to The Billboard Book of No. 1 Hits, Wonder demanded a half-million advance for the sample. (Wouldn’t you?)

On the 1999 MTV Movie Awards, Wonder, now an elder statesman, helped promote his latest lucrative copyright with a live cameo during Smith’s performance of “Wild Wild West.”* Smith probably needed the assist by the time of the show—Wild Wild West, the movie, had been a troubled production and wound up as that summer’s most notorious bomb. And yet, there was Stevie, gamely singing Smith’s dopey revamp of his lyric (“Goin’ straight! To! The Wild Wild West!”). Three decades after helping his Motown elder Smokey to a No. 1 hit, 49-year-old Stevie Wonder was bestowing another on a new generation.

Correction, Dec. 21, 2016: This article originally misstated the MTV award show on which Will Smith’s “Wild Wild West” was performed with Stevie Wonder. It was the 1999 MTV Movie Awards, not that year’s Video Music Awards.

Content retrieved from: http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/wonder_week/2016/12/the_songs_stevie_wonder_wrote_for_michael_jackson_smokey_robinson_and_others.html.