XXXTentacion’s No. 1 Hit Presents the Ultimate Music-Industry Test of the #MeToo Age

Though he’s far from the first troubled victim of gun violence to go to No. 1.

Serial killer Charles Manson’s only studio album was released while Manson was being held on charges for the two-night series of 1969 killings he instigated via his “family” cult, known as the Tate–LaBianca murders. Morbid curiosity couldn’t, however, make Manson’s groovy, psychedelic acoustic-folk album a hit. Issued on a tiny indie label in 1970, only a few hundred copies sold out of only a couple thousand pressed. The music on Manson’s album, however, has proved oddly, stubbornly resilient: Its leadoff track was remade by Guns n’ Roses on their platinum 1993 covers album, alt-rock band the Lemonheads covered a contemporaneous Manson demo recording, and Marilyn Manson—an artist whose stage name was adapted from Charles Manson’s—incorporated lyrics from his namesake into his own 1994 song “My Monkey.” Over the decades—as Manson sat in prison, right up until his death last fall—Lie was reissued numerous times on a spate of labels. It is probably safe to guess it has sold tens if not hundreds of thousands of copies, and to this day, it doesn’t go out of print for long.

Consider the above a fulfillment of the music-industry equivalent of Godwin’s law: I am invoking an extreme example of outsider music, made by possibly the most horrific recording artist of the rock era, to make an imperfect and at least somewhat unfair analogy. On the one hand, there is nothing at all new about notoriety, even of the kind borne of violence, increasing the public’s interest in that artist’s musical output. Nor is it particular to any genre. On the other hand, Charles Manson didn’t record in the era of digitally fueled pop charts. For years, Lie was passed around on bootlegs. There was no YouTube, no social media, no easy way to make Manson’s music go viral. Which explains why our understanding of Manson’s sales is so murky.

We don’t have that issue anymore. And the result—after a week of morbid curiosity coupled with genuine, rabid fandom—is a new Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 song, one most critics and even a large portion of the industry would prefer never became a hit. It’s a song I doubt you’ve heard on the radio and probably never will.

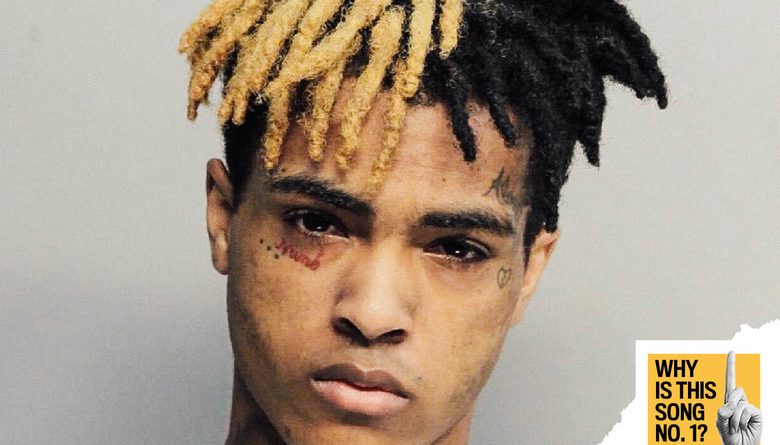

That song is “Sad!” by the now-late recording artist XXXTentacion. It was already a Top 10 hit, the artist’s first, before X—as most fans and reporters called him colloquially—was killed in a Florida shooting at age 20. The song reached its original peak back in March. The former No. 7 hit had fallen out of the Top 40 during the spring and sat at No. 52 the week X was gunned down in an apparent botched robbery in Deerfield Beach, Florida. In the wake of his death, an outpouring of streaming activity on Spotify, YouTube, and other on-demand sites, plus solid increases in the now old-school medium of paid downloads, fueled a 51-place comeback by “Sad!” to the Hot 100’s top slot. It’s certainly not the first posthumous No. 1 hit in Hot 100 history—more on that in a moment—but it’s the biggest leap to the top by a just-deceased artist ever, made possible by the mix of digital data that now powers the chart.

As my Slate colleague Jack Hamilton chronicled last week on the occasion of his death, the 20-year-old born Jahseh Onfroy was too complex an artist to call simply “a rapper.” Influenced by grunge, emo, rap-rock, and indie music, much of which came out before he was born, Onfroy’s music passed through multiple genres not just from song to song but sometimes within songs. He didn’t just sing, as does Drake and any number of other rappers, he essentially recorded a kind of low-fi indie rock nearly half the time. “Sad!” is actually a somewhat more typical hit by modern hip-hop standards, in that it rides a minor-key trap-synth hook. Even though X sings all the way through it, his cadence echoes the singsong flow of a Future or a 21 Savage. Like another bummer hip-hop-adjacent act we just discussed in this series a couple of weeks ago—Post Malone, whose “Psycho” spent a lone week at No. 1 in mid-June—XXXTentacion offers further evidence that hip-hop has so expanded as a genre that it is now all-encompassing, the way so-called rock came to mean all of popular music a couple of generations ago. A Rolling Stone encomium for XXXTentacion, all but guilt-tripping music fans to appreciate the late musician’s musical accomplishments, claims—fairly—that Onfroy will go down as the signal artist of his “SoundCloud rap” generation: morose, multigenre, mellifluous.

We can also add a fourth M-word to the description of Onfroy: monstrous, which explains a great many music fans’ reluctance to consume his music at all. Even beyond the well-supported allegations that he denied until his death, the things Onfroy openly admitted to doing are horrific: beating a middle-school girlfriend to get the attention of his oft-absent mother, beating a fellow juvenile-detention inmate nearly to death for looking at him with perceived same-sex lust, denying his ex-girlfriend’s criminal charges (for these, Onfroy was arrested: allegedly beating her for years, including while she was pregnant, and even imprisoning her) with an intemperate declaration about what he would do to his accusers’ little sisters’ genitalia. I needn’t recap it all—like many others, I commend to you Miami New Times writer Tarpley Hitt’s masterful profile. After reading it, you may think my analogy of Onfroy to Charles Manson—despite the former’s lack of history as a serial killer—isn’t all that outrageous after all. You may also want to take a shower.

As Billboard reports, XXXTentacion’s posthumous No. 1 hit places him in the company of five other lead artists who hit the top after leaving this life: Otis Redding, Janis Joplin, Jim Croce, John Lennon, and the Notorious B.I.G. (Two other deceased artists, both ’00s rappers—Soulja Slim and Static Major—were credited as featured acts on the No. 1 hits “Slow Motion” by Juvenile and “Lollipop” by Lil Wayne, respectively.) While X’s fellow posthumous chart-toppers put him in heady company, you can actually subdivide these half-dozen deceased song leaders further, based upon the way they died. The first three experienced what could fairly be termed accidental deaths. Redding and Croce both died in plane crashes: The former’s “(Sittin’ on) the Dock of the Bay” hit No. 1 in 1968, two months after his tragedy, and the latter’s “Time in a Bottle” peaked at the end of 1973, three months after his. Joplin, whose “Me and Bobby McGee” reached the top in 1971, had died five months earlier from a heroin overdose.

It’s the other two lead artists who form a much more exclusive three-man morbidity club alongside XXXTentacion: posthumous chart-toppers brought down by a gun. Lennon’s kitschy, ’50s-esque “(Just Like) Starting Over” hit No. 1 in late December 1980, about a fortnight after his assassination by deranged fan Mark David Chapman—an event that instantly made the song’s lyrics (“Our life together/ Is so precious, together”) unbearably sad and ironic. A little more than 16 years later, in March 1997, Christopher “Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace was gunned down in a still officially unsolved drive-by shooting in Los Angeles. About two months later, in early May, Biggie’s Herb Alpert–sampling banger with Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, “Hypnotize,” crowned the Hot 100. Biggie actually scored two posthumous No. 1s, the only artist to do so—three months after “Hypnotize,” he was back on top with his flossy, Puffy and Mase–supported, Diana Ross–sampling summer jam “Mo Money Mo Problems.” XXXTentacion’s posthumous chart-topper is the first by a lead artist in nearly 21 years, since “Problems” departed the top slot in September 1997.

These three gunned-down chart-toppers have even more in common, however: a history of toxic male behavior. The more facile analogy is between X and fellow rapper Biggie Smalls. Given his association with the peak of ’90s gangsta rap, Biggie did indeed possess a sizable police record, albeit one largely composed of fairly run-of-the-mill criminal activity akin to that of now-respectable citizen Jay-Z: drug dealing, gun possession, low-level robbery. He was also arrested for, and/or settled, two accusations of assault—one involving a concert promoter and the other an autograph-seeker. These actions shouldn’t be minimized, but (I realize this is a low bar) there was no violence in his record as sadistic or recurring as the acts for which Onfroy was arrested.

The more uncomfortable parallels are with the man who never spent a night in jail, John Lennon. I am about as big a Beatles fan as they come and love Lennon’s oeuvre, but it must be said that, though he died an über-progressive feminist, Lennon’s history is pockmarked with acts that would, rightfully, never pass muster in the social-media age. By Lennon’s own admission, he was a recurring girlfriend- and wife-beater. (It’s right in the lyrics of the 1967 Sgt. Pepper cut “Getting Better”: “I used to be cruel to my woman, I beat her and kept her apart from the things that she loved.”) Spookier: Like X, Lennon beat a man almost to death for implying he was gay. This does not even include his checkered history as an absentee dad to his first child and as a public mocker of the disabled (the latter giving him more in common with our current president). While Lennon turned out far more self-aware, and less sadistic and deranged, than this week’s chart-topper ever became in his two decades on this earth, the parallels between the former Beatle and XXXTentacion are discomfiting—not least the fact that both were birthed by absentee mothers, regarded in both cases as the source of their dysfunction.

If we could place the #MeToo movement in a time machine and send it back to 1967, Lennon would receive withering scrutiny. In the wake of X’s death, numerous figures in the hip-hop community commemorated his work and, with caveats for his crimes, came to his defense as an artist via tweets, Instagram posts, and other comments. It is generally agreed the most eloquent tweet series came from Jidenna (the rapper behind the 2015 hit “Classic Man,” also familiar from 2016 Best Picture winner Moonlight): “For those who are so woke that their compassion is asleep, remember this…if Malcolm X was killed at the age of 20, he would have died an abuser, a thief, an addict, and a narrow-minded depressed & violent criminal. So, I believe in change for the young.” It may be hard to imagine reform from someone so sociopathic—one might instead picture an Onfroy who lived into his 30s fighting his demons in a manner more akin to the still-troubled chart-topper Chris Brown. However, what Jidenna says about 20-year-old Malcolm X could also apply to a 22-year-old John Lennon, the year he beat a flirtatious gay man at a birthday party to a pulp.

Back to the charts, and what finally sets XXXTentacion apart: The reasons Lennon’s “Starting Over” and Biggie’s “Hypnotize” became swift No. 1 hits in the weeks after their respective deaths were that each artist was already a superstar, and each single was on the rise on the charts. “Starting Over” was in the top five the week Lennon was murdered. When Biggie was gunned down, “Hypnotize” was already a Top 40 radio hit, and when its retail single dropped a month later, it debuted all the way up at No. 2 before ringing the bell one week later. Both performers were megastars, and however questionable their pasts, each died more beloved than they were scorned. Fans went into record stores to consume their output and mourn their losses, not learn who they were.

None of the above was true of XXXTentacion at his death. “Sad!” was three months past its peak the week he died, and X was far less known to a great majority of the public. Indeed, a segment of the public was actively, as the phrase goes, not trying to hear that: The “woke” impulse among critics and cultural gatekeepers—akin to the recent #muteRKelly movement—was to give X’s music as little airtime as possible. (This continues after X’s death—on last week’s edition of the New York Times Popcast, critic Jon Caramanica managed an excellent hourlong audio discussion of X’s career with multiple guests without playing a note of X’s music.) The tacit, year-plus agreement to mute XXXTentacion didn’t prevent him from scoring a pair of chart-topping albums: 2017’s No. 2–peaking album 17, and this year’s No. 1–debuting album ?, each fueled largely by young fans streaming the bejeezus out of their tracks. But it doesn’t take much to score a top album for a week—many weeks, rousing the fan base is enough to ring the bell. To top the Hot 100, generally, you need some form of cultural ubiquity and widespread consumption.

With one major hand tied behind his back, X managed to top the chart anyway. Streams were massive—Billboard reports nearly 50 million streams for the week, a number that would be a solid week for someone like Drake—and sales were sizable if not mind-blowing, about 26,000 downloads. The lagger is, you guessed it, airplay—the radio audience for “Sad!” is less than 3 million. And this gets to the crux, the biggest difference between 2010s chart-topper XXXTentacion and the posthumous bell-ringers of yore: Given his exceptional lack of radio airplay, if you, curious listener, want to find out what X’s music sounds like, any legal medium on which you choose to consume him will count toward the charts: Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube. If you have decided X deserves his public opprobrium but want to hear him anyway, you practically have to be an outlaw to sample his wares—the equivalent of buying a Charles Manson bootleg LP in the ’70s.

The history of the Billboard charts is the history of better data and improved technology giving us a fuller picture of just what music Americans are consuming—even the music they’d prefer we didn’t know they were consuming. The launch of Soundscan on the charts in 1991 revealed that N.W.A wasn’t a fringe act of hip-hop outlaws, they were a chart-topping crew, one of the biggest groups in America. The invention of the radio-measuring device the Portable People Meter in the 2000s revealed exactly what radio stations folks were consuming in their daily byways—even in public places—not what they said they were tuning into. In the 2010s, the addition of streams and YouTube to the Hot 100 means virtually every last corner of legit music consumption is tracked by Nielsen Music and fed into the charts.

So I find myself asking—again, as I asked six weeks ago, when Childish Gambino’s video-fueled “This Is America” topped the chart: Is this now just a straight-up hit song? “Sad!” is the ultimate test of the Hot 100 not just as a hit barometer, as I so often call it, but as a hit-fueling feedback loop. I am hard-pressed to think of an artist who topped the Hot 100 after this level of almost Manson-like societal scorn. I must report, with not a small amount of queasiness, that “Sad!” is a catchy, enveloping, and enticing record, more obviously radio-friendly than the more jarring, rhythmically lurching “This Is America.” “Sad!” is even an ideal single length—under three minutes, a succinct soul-baring statement that doesn’t wear out its welcome. Except for its creator, who is unwelcome for all sorts of good reasons.

If there’s one way I mildly disagree with my colleague Jack, who in his article professed not to enjoy X’s music, I must confess that, divorced from its context—and I am turning off my conscience when I say this—a lot of his music hits my Gen-X pleasure centers. If you are a mid-to-late-fortysomething like me, and you listen to full albums by XXXTentacion, you may be shocked at how warmly familiar a lot of it seems. Several of X’s tracks are just awful, but on his best songs, X’s music resembles a low-fi ’90s Guided by Voices track reinterpreted by a misguided kid from Florida who only occasionally raps. I can’t emphasize this enough: I do not find XXXTentacion’s music amazing enough to recommend you access it, and in terms of musical talent, he is no Biggie or John Lennon. I did so for journalistic reasons (to assuage my guilt, I listened to the tracks via another user who’d already acquired them by his own means). Now that “Sad!” is a No. 1 hit, however, you may be exposed to it whether you like it or not. Brace yourself for the ultimate test of music-industry gatekeeping in the age of #TimesUp, involving an artist whose time is already up.

Content retrieved from: https://slate.com/culture/2018/06/why-xxxtentacions-sad-is-no-1-on-the-hot-100.html.