100 & Single: Considering The Album-Chart Class Of 9/11, 10 Years Later

A king of hip-hop, retaking the penthouse of the album chart with his latest blockbuster.

A middle-of-the-road rock band, reviving a turn-of-the-’90s “alternative” sound that’s now squarely mainstream.

A sexagenarian legend who debuted in the ’60s and who still captures Boomers’ hearts and CD-buying dollars.

And a younger, big-lunged diva, looking to continue her pop dominance after a notable MTV appearance and a blitz of multimedia omnipresence.

I could be describing some of the current inhabitants of the Top 10 of the Billboard 200 album chart. If I were, they would be, respectively: rap king Lil Wayne, who debuted at No. 1 this week with nearly a million in sales; aging alt-funksters the Red Hot Chili Peppers, debuting right behind Wayne at No. 2; ’60s ingénue turned veteran diva Barbra Streisand, at No. 9 in her third week in the winners’ circle; and vocal powerhouse Adele, hanging in at No. 3 after a commanding MTV Video Music Awards performance that, just this week, sends her ballad “Someone Like You” to No. 1 on the Hot 100.

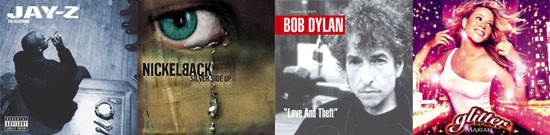

But I could also be describing four acts who, on this day a decade ago, dropped new, Top 10-destined albums: hip-hop king Jay-Z; lite-grunge revivalists Nickelback; reluctant ’60s-generation spokesman Bob Dylan; and pop/MTV queen turned ill-fated actress Mariah Carey.

That day, as you’ve heard friends and pundits reminisce, was a lovely one in New York City—perfect weather, blue sky. More important for our purposes, the day now called 9/11 was a Tuesday, which meant it was an album-release day. Not that anyone in my hometown was buying CDs.

What’s my point? That, in popular music as in life, the more things change, the more they stay the same? Sure, that’s true—there was even a NOW compilation in the Top 10 back then, and another one’s in the Top 10 now—if a little obvious.

As a chart-watcher, I’m consumed with the idea of mass art as unintentional art. Week after week, my colleague Al Shipley and I use this space to make readers aware of music whose popularity demands that we reckon with it, for better and worse. (The fact that we genuinely like a good deal of this stuff is immaterial.)

Albums that reached the world on 9/11 are, in a way, the ultimate unintentional art. These albums landed, unwitting and fully formed, into the post-9/11 world. None of these are among the roughly half-dozen Great Works my fellow critics have nominated as “9/11 albums,” from prophetic records like Kid A and Yankee Hotel Foxtrotto direct responses like The Rising. These, instead, are the albums that had to find the mass audience they were intended for in the fourth quarter of 2001—a time when such an idea felt, momentarily, a bit vulgar.

Some of them actually are great art, amazingly. And what’s sort of remarkable about the half-dozen 9/11 releases that materialized in the Top 10 of the Billboard 200 is that they span at least four, maybe five or six sub-genres, and offer a window into how the pop world would reconstitute itself over the next decade—including how certain mini-genres were ultimately doomed in the new century.

I don’t want to make too much of these albums as comments on our world, unwitting or not. But I do think it’s valid to consider what we were consuming then, and whether the anxious decade to follow changed our perception of these discs.

Jay-Z, “Izzo (H.O.V.A.)”

First, a technical note: None of these albums appeared on charts dated September 11. In 2001, even with the wonders of Soundscan, tallying album sales took a little while. To be specific, first-week sales for the 9/11 releases were tallied by September 18, announced by Soundscan by September 20, and published by Billboard in a magazine dated Saturday, September 29, 2001.

On that September 29 chart, six albums debuted in the Top 10 of the Billboard 200, all of them 9/11 releases. All debuted where they ultimately peaked on the chart. Here they are, with their chart position shown beforehand and their sales—first week in 2001, total sales as of 2011—in parentheses.

No. 1: Jay-Z, The Blueprint (426,000 first week, 2.7 million cumulative): Rap’s self-proclaimed Frank Sinatra has, as of this writing, topped the Billboard 200 a dozen times, more than any act except the Beatles. Indeed, even back then, Jay was amassing an epic chart streak—at the time, Billboard columnist Geoff Mayfield marveled that Jay managed to move nearly a half-million albums despite the week’s tragic disruption.

But it’s notable that the chart-topping disc he happened to drop on 9/11 was, and is, widely considered his greatest. And The Blueprint didn’t need an ode to New York a la “Empire State of Mind” to feel like a love letter to Jay’s now-suffering city. Of all the Top 10-destined albums from that day, The Blueprint arguably has the longest and strongest legacy, even if the man who made it continued to live in its shadow.

In the decade to come, Jay appeared to take the title of his 2001 album literally, releasing three more Blueprint-branded discs. Such titling has done more for the sequels’ sales—the hit-laden Blueprint 2: The Gift and the Curse actually outsold its predecessor—than their acclaim (2003’s The Blueprint 2.1, in particular, prompted grumbling from critics and fans).

But the original Blueprint also pointed toward the way major-label hip-hop would evolve after the fin de siècle ghetto-fabulous era. It represented the debut, in the background, of tyro producer Kanye West, who manned the boards for the album’s joyous hit “Izzo (H.O.V.A.)” and classic beef track “Takeover.” In fact, West’s later, stellar body of work under his own name was the true legacy of The Blueprint‘s sonic omnivorousness and urbane confidence. While hip-hop in the early 2000s would have one last flirtation with the gangsta ethos in the form of 50 Cent and coke-rap, the more contemplative tone of late-decade rappers like Lupe Fiasco and Kid Cudi owes its existence to The Blueprint.

Nickelback, “How You Remind Me”

No. 2: Nickelback, Silver Side Up (178,000 first week, 5.5 million cumulative) Silver Side Up, with its effective, minimally creative take on post-grunge, wasn’t Chad Kroger & co.’s first album. It wasn’t even their first popular album; their 2000 sophomore disc spawned a handful of rock-radio hits and eventually went gold. But Silver effectively served as their pop coming-out. Its fungus of a lead single, “How You Remind Me,” was already atop Billboard‘s rock charts when 9/11 happened, and it would spend another three months there. By Christmas, the song it would sit atop the Hot 100, the last straight guitar-rock song to top the big pop chart (not counting Coldplay’s stringy/synthy “Viva la Vida” in ’08).

Nickelback’s legacy as a chart juggernaut can’t be denied. Even more than Jay-Z, they were a model of sales consistency over the next decade, consistently debuting at No. 1 or No. 2 and outselling everyone except Eminem. Each of their post-2000 albums is at least triple-platinum, and their 2005 disc, All the Right Reasons, is one of the record industry’s few post-crash albums to go as high as septuple-platinum (only discs by Norah Jones and Carrie Underwood have matched that mark).

Usually stuff as popular as Silver has an artistic legacy as well. But it’s hard to point to much that Nickelback has inspired besides their own staggering sales. The mainstream and modern rock charts have been awash in similar lite-grunge bands for most of the last decade, but it’s been to steadily diminishing returns. Nickelback’s 2001 contemporaries, including Creed, Staind and Puddle of Mudd, either burned out or faded away, and newer rock acts a decade later, like Cage the Elephant, have smaller radio hits and corresponding sales.

In the absence of a major country album among the 9/11 releases, it’s tempting to fill that slot with Nickelback, a bunch of Canadians whose heartland-friendly sound made them unhip but perfectly attuned to red-state tastes. But as strong as their sales have been, mostly Nickelback were—and this is, in a way, poetic if depressing—the beginning of the end for a genre. If anything pointed the way toward rock’s demise as a pop medium, Silver Side Up was the ferryman on rock’s river Styx.

No. 4: Fabolous, Ghetto Fabolous (143,000 first week, 1.1 million cumulative): The difference between Jay-Z and fellow Brooklynite Fabolous would appear to be one of degree of fame, not genre or ambition. Not deeply beloved and certainly not critically acclaimed—in a recent poll I conducted of rappers’ album ratings, he came in dead last—the man born John David Jackson nonetheless made an impressive 2001 chart debut, splashing into the Top Four on the strength of his summer hit “Can’t Deny It.”

Among the 9/11 releases, Ghetto Fabolous doesn’t have a terribly impressive legacy. But it is a near-perfect distillation of what hip-hop’s second and third tier of stars would look like as the medium entered its third decade. If The Blueprint is hegemonic, commanding rap, Ghetto Fabolous is middle-class radio rap. The former can be imitated but rarely equaled; the latter is reheated on the radio every day.

In Hollywood and on Broadway, there’s a term the rank-and-file use to describe themselves, with a mix of both pride and regret: working actor. It means, “I’m recognizable but not a star, and probably never will be—but hey, I’m here, and I’m earning.” As hip-hop settled into middle age, the concept of “working rapper”—the medium-size radio presence who relies on numerous guest spots and a steady flow of product to get over—became a viable career path.

Some, like Lil Wayne and T.I., converted the working-rapper approach into full-blown megastardom by the decade’s end. Others, like Fabolous and Ludacris, settled into very comfortable careers as reliable product-shifters and radio voices. Sure, they’re stars—in their presence, I wouldn’t call them anything less—but they’re stars of the unapologetically workmanlike variety. Where, before 2000, rap hits generally got by with a guest star or two, now four- or even six-rapper team-ups are common. Just since 2009, Fabolous himself has had lead credit on just five R&B/Hip-Hop chart hits but taken “featured” credit on another 12 hits. The omnipresence of the working rapper, and his strengths and limitations of his pop horizons—if Fabolous helped spawn anything, that’s it.

P.O.D., “Alive”

No. 5: Bob Dylan, Love and Theft (134,000 first week, 773,000 cumulative): Of all the albums to debut on 9/11, you’d expect Dylan’s to be the one packed with Statements. In fact—and not just because he recorded it before the horrors of its release date—Dylan seems on Love and Theft to be actively avoiding statements of any kind.

The album that, four months later, would dominate the 2001 Pazz & Jop poll was received by critics as a kind of balm, but a great one. Robert Christgau described Love and Theft as both Dylan’s “immortality album” and “profound, too, by which I mean very funny.” It likely would have been the year’s most acclaimed album regardless of world events. Given the long lead times of 2001’s still print-dominated media, most reviews of the album were written in the weeks before its release—meaning that not just Dylan himself but also his many professional admirers contended with the album well before 9/11.

Record buyers, on the other hand, acquired Love and Theft in the days after the tragedy, which may partially explain the disconnect between the rapturous critics and the less awestruck masses. Certainly, the disc’s impressive Top Five album-chart debut benefited from the afterglow of Dylan’s 1997-98 comeback; its predecessor Time Out of Mind gave him his first-ever Album of the Year Grammy and ultimately went platinum. That Love and Theftultimately only went gold may indicate that Dylan in charming-old-rogue mode was not the Dylan the earnest masses were looking for after 9/11.

Oddly, the folky Americana of Love and Theft found its home not at fall 2001’s dozens of memorials, but at the nation’s thousands of coffee shops, helping to kick off music’s Starbucks decade. From 2000’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack (which by September 2001 was months away from its own Album of the Year Grammy) to future NPR-friendly blockbusters by Norah Jones and Ray Charles, adult-oriented music in the 2000s stopped trying to compete with pop currents and took refuge from the radio, in the realm of the barista. By 2006, Dylan was scoring chart-topping albums like Modern Times that were promoted heavily at Starbucks outposts. It could be said that ol’ Zimmy, once a coffeehouse folkie, came full circle—even if the sound of a milk steamer diminished his latter-day output.

No. 6: P.O.D., Satellite (133,000 first week, 2.9 million cumulative): What’s most dated about P.O.D.’s breakthrough album a decade later? The bro’d-out baggy-pantsed cover? The Bizkity crunch of its guitars and flat-toned rapping? The pre-Faith Plus One earnestness of its Christian lyrics? Mock all you want, but this time capsule of a disc is the second-best-selling of the 9/11 releases, outdoing even Jay-Z’s classic and second only to Nickelback’s disc.

It’s also got its moments, especially the postpunk-like chime of the guitars on “Youth of the Nation,” the radio smash that probably propelled this album through at least two of its three platinum certifications. (The rapping on that song is, let’s say, somewhat less impressive.) That song, P.O.D.’s biggest hit—it topped Billboard‘s Modern Rock chart in 2002 and even made the Hot 100’s Top 30—remains their most enduring legacy, a radio-gold track to this day.

More precisely, Satellite was to rap-rock in 2001 what Slaughter’s Stick It to Ya was to hair-metal in 1990: the last multiplatinum breakthrough before a rock mini-genre was declared obsolete. While P.O.D. themselves and several of their peers—Korn, Papa Roach, 311—quietly continued scoring rock hits deep into the aughts and could rely a solid base of fans, never again after Satellite would a rock-rap album collect armies of casual pop-radio listeners. (Limp Bizkit, the genre’s ultimate avatar, fell harder; after selling at sextuple-platinum levels in 1999 and 2000, they could barely break gold after ’01, so deep was their uncoolness.)

Of course, P.O.D. had an affiliation with Christian music fans, an especially loyal category. But the band, whose name stands for Payable on Death, has been careful, since its embrace by the mainstream, not to remain pigeonholed; late in the decade they said they didn’t “adhere to any one religion.” This is the more subtle cultural shift P.O.D. represents in the decade since 2001. Culture wars notwithstanding, Christian rock in the late 20th Century was an acceptable, if sporadic, means to rock crossover, from Stryper in the ’80s to DC Talk in the ’90s. But even as praise-related music continues to sell well, the 2000s have seen rock acts, in particular, more desperate to flee the Christian genre ghetto, including a particularly messy break by Evanescence in 2003. It’s of a piece with the harder battle lines drawn between evangelicals and mainstream popular culture during the decade.

Mariah Carey, “I Didn’t Mean To Turn You On”

No. 7: Mariah Carey, Glitter (soundtrack) (116,000 first week, 773,000 cumulative): Few career pivot points are as bright, obvious and deadly as Glitter—the movie showed that Mariah Carey wasn’t destined to be an actress, and the soundtrack-cum-pop album showed that EMI wasn’t destined to further Mariah’s career. Garth Brooks is still teased in the media for his whacked-out Chris Gaines project, but he came back instantly with a string of multiplatinum albums. Not only has Glitter, Carey’s lowest-selling album, become a synonym for “career bomb,” but Carey, arguably, never fully recovered.

One doesn’t make such statements lightly; I’ve been flogged by Mariah’s loyal and loud army of fans before. But as amazing as Carey’s mid-2000s comeback with The Emancipation of Mimi and “We Belong Together” were, that triumph followed a deep, half-decade hole of Top 40 absence; and it was followed by a short run of 2005-08 hits and a return to pop-radio indifference. It’s silly to count Mariah out, given her catlike ability to generate new lives. But no pop act, no matter how mighty, has more than one period of total dominance. Elton John and Madonna still record profitably and draw crowds—but the former will never have another ’70s, the latter another ’80s. Carey, the pop star of the 1990s, will reclaim moments of her peak glory, but only that, moments.

More fundamentally, the Glitter debacle had to happen, because pop had to change. What was impressive about Carey in the ’90s was her ability to surf several radio trends: diva-melisma pop early on, hip-hop-derived pop mid-decade, and pure pop during the late-’90s Britney/Xtina boomlet. By September 2001, however, pop was spent as a cultural force. On the album chart in which Glitter made its debut, Carey’s was the only pop album in the Top 10; that very week, *N Sync’s last blockbuster, Celebrity (with the apropos lead single “Pop”), vacated the album-chart Top 10 only two months after its release, never to return.

It’s logical to credit 9/11, with its Changing of Everything, for the move away from pop—and surely, none of the six major albums released on 9/11 seemed less appropriate to the new normal than Glitter. (Good god, that title!) But that’s facile and easily disproved; the ongoing chart dominance of Jennifer Lopez—No. 1 on the Hot 100 with “I’m Real” at 9/11 and for weeks afterward, and back on top multiple times in 2002—shows escapism still sold on the radio after the tragedy. What actually happened after Glitter was a half-decade shift toward hip-hop/pop and a hibernation for pure pop, until songs like Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl” paved the way for the current female-pop boomlet. Pop, as it often will, morphed—away from showy vocal dynamos like Carey and toward self-mythologizers like Lady Gaga.

During this week of 9/11 look-back across the media, numerous cultural commentators have bemoaned the fact that the disaster didn’t change art or culture in any fundamental way, at least in terms of seriousness of purpose. What the album class of 9/11 shows is that the cultural changes wrought by world-altering events are always more subtle than the event itself. It’s not even demonstrable that world events ever have, or have ever had, much effect on mass art. The folk movement of the early ’60s was in full swing before Vietnam, and rock’s move toward album-length statement in the late ’60s was going to happen in some form regardless of the protest movement.

Likewise, the 21st century atomization of pop was going to happen even if the terrorist plots had been blessedly foiled. If 9/11 had any effect upon pop, it was merely to deepen those divisions, making the walls around our cultural gardens higher than ever. The wonder, honestly, is that we ever come together at all—whether it’s for something as heavy a 9/11 memorial or something as pleasurable as an Adele album everybody from kids to grandmas decides to adopt. Happily, occasionally—even in our post-monoculture age—it does still happen.

Content retrieved from: https://www.villagevoice.com/2011/09/11/100-single-considering-the-album-chart-class-of-911-10-years-later/